It seems that when people tell their history, especially about people that are no longer living, that the stories become bigger, better, different than they were originally, or in some cases completely manufactured. That said, most of them are based on at least a grain of truth. Thus, they can’t be completely dismissed.

Key Elements

A good genealogy story – not a true one, but a good one that intrigues people and gets them interested in the family – are made of at least one of the following: an illicit affair, ties to Native Americans, being born on a ship to America, the Mayflower, Salem, Capt. John Smith, a rich relative, and/or connections to famous people. Bonus points are given for any story that incorporates multiple key elements into one story.

The problem is that people believe these stories no matter how little data supports their story. One of my family stories with little actual evidence is the case of my family’s alleged ties to President John Adams.

The Story

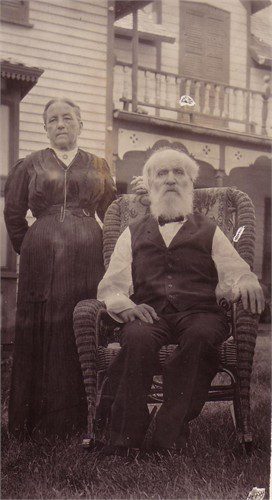

According to distant cousins, 4th great grandmother Tabitha, who married the earliest known Passco Peelle (not the earliest Peelle, but the earliest Passco), was the illegitimate daughter of President John Adams. And, some of the family notes say that she was the daughter of both John Adams and his later wife Abigail Smith.

This story was based on family lore and a few notes and letters that were written years after Tabitha’s death that supported the story. Additionally, Passco and Tabitha’s grandson William Peelle’s middle name was Adams, which seemed to support the story.

Schroth-Peele Research

In 2015, Milton N. Schroth, a descendant of Tabitha and Passco through great-grandpa William Johnson Peelle’s sister Rachel, and Horace B. Peele, a longtime Peel/Peele/Peelle researcher and far distant cousin, published the results of their extensive research into Tabitha’s lineage in the Peelle Newsletter. Down load Volume 15 Issue 1 of the Peelle Newsletter to read the results of their investigation.

Their Conclusions

In their research, they examined numerous aspects of this claim, including John Adams’s history with women, ages of people involved, Tabitha’s lack of verifiable history, the handwritten document that listed John Adams as Tabitha’s father, and more. I will not reiterate their entire stated research. However, they found that they could not prove it false and believed that the evidence that did exist supported the claim.

On the other hand, they decided that the claim that his later wife Abigail Smith was Tabitha’s mother was not true despite that being part of the notes they had. This was based on her age and health. So, they believed part of the story. That is not unreasonable given that stories that are passed down are usually partially true, but rarely completely true.

Questioning The Conclusions

At the time, I corresponded with both the authors, whom I had previously discussed family history, stating my questions and concerns. I was assured that if I had seen all the research they had done that I would not question the outcome. That answer was not satisfactory to me and I continued to question this claim.

Since their research has been widely circulated and this connection to President John Adams is now all over ancestry.com, I feel that it is appropriate to share questions about the story. I am not saying that we are or aren’t related to John Adams. I just have a lot more questions before I claim him as an ancestor.

My Specific Questions

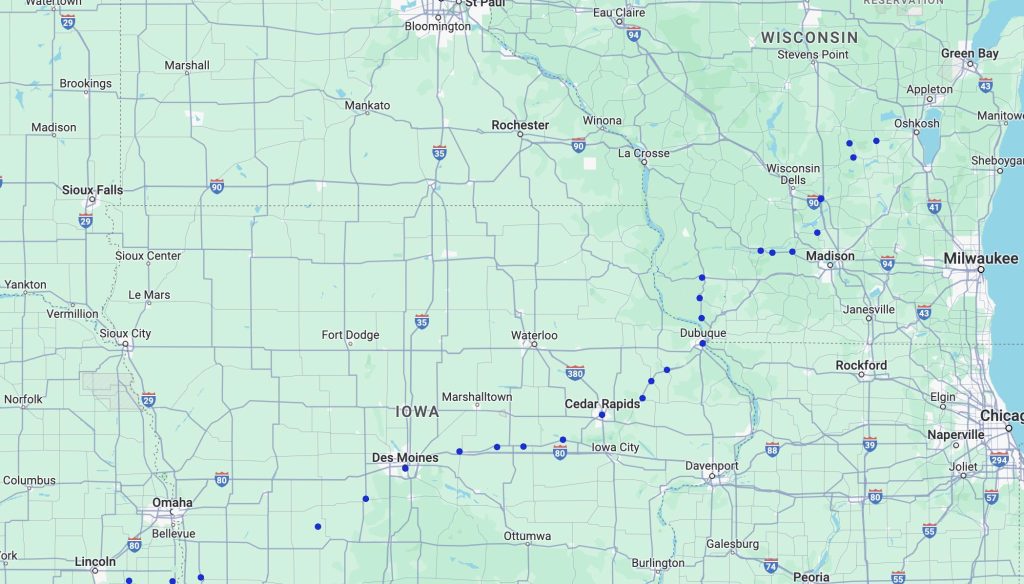

Location, Location, Location

The first question that came to mind was that Passco lived in North Carolina. Thus, it is assumed that he met Tabitha there. If her biological mother got pregnant by John Adams, it is likely that occurred in the Boston area. So, was the mother sent to family or friends in North Carolina to have the baby? Was there a story of Tabitha’s mother’s “husband” dying (a common cover for a child out of wedlock)? Was Tabitha sent to North Carolina after her birth to be raised by or adopted by a family? Did a well-to-do family pay someone to raise her? Why so far from Boston?

What Is In a Name?

Tabitha’s last name was said to be Dunigan. However, I have never found a record that shows her maiden name. In addition, there are lots of versions of that name. Many spelling options exist at the time of her birth and many people didn’t know how to even spell their own name. Yet, it is unclear if that is supposedly her mother’s name, adoptive parents name, or where the name came from exactly. Additionally, I have found zero proof that her name was Dunigan. Was that name passed down in the family? Did somebody get the name wrong?

Missing Records

One contributing factor was that they could not find a record of Tabitha’s birth or of her parent’s names. Tabitha most likely married around 1775. Thus, most records regarding her birth and parents would likely have been recorded pre-Revolutionary War. It is not at all unusual to encounter a lack of records in that era even for a Quaker.

I saw an article once where I believe it was Tabitha that claimed she did not know her age. The reason why was that the meeting house with the records had burnt. This is very possible and could definitely explain a lack of records as numerous Quaker meeting houses (and churches in general) burnt in the early years of our country. Since the Peelle family were Quakers and no record exists of Tabitha and Passco’s marriage or the birth of at least many of their children, it seems very likely that records of the family were lost, which makes the lack of records inconsequential and clearly not an indicator that someone was trying to hide Tabitha’s history.

So, why did anyone assume that missing records equate to supporting the story? Aren’t missing records in genealogy expected? Especially in the 1700s?

Adams Middle Name

Passco and Tabitha’s grandson being named William Adams Peelle would seem to strongly corroborate the story until you realize that another ancestor of mine named Sarah (Adams) Johnson lived in the area and her ancestors were from North Carolina as were the Peelle ancestors. Additionally, there were two other Adams family in Wayne County, Indiana around the time of William’s birth. Couldn’t they have named him Adams after one of these people? Or, couldn’t they have named him after the President without him being Tabitha’s father? After all, people named their kids after presidents all the time.

Additionally, they stated that John Adams and his wife had died by the time William Adams Peelle was born and so there was no worry of a scandal. However, this is incorrect. His wife Abigal had died. However, President Adams did not die for several years after William Adams Peelle was born. Besides, who would have known that the middle name of Adams had any relevance to the person’s grandmother’s father unless someone in the family went around telling the story? So, it would seem that anybody in the family at any time could have been named Adams without starting a scandal.

Tabitha’s Birth

When was Tabitha born? The conclusion that the authors of the research had was about 1755. Others have assumed that as well based on the ages of her children. According to Quaker records, Anna born in 1778 is Tabitha’s daughter. If we assume that Tabitha is the mother of all the known children of Passco, then she was child bearing from 1775 – 1795. Thus, they assumed that she was about 21 when the first child was born in April 1776 and that she was approximately 40 when her last child was born. This is a reasonable assumption for searching for records. However, Tabitha’s exact birth year is very important when determining if John Adams was indeed her father.

Childbearing & Age

If I look at reasonable child bearing years, Tabitha could have been as young as 13 with her first child or as old as 50 with her last child. This places her birth sometime between 1745 and 1762. If we then apply the 1800 census, we find that the oldest female in Passco’s household was marked as 45 and over. Thus, this reduces the interval that Tabitha could have been born to 1745 to 1755.

Passco was born in 1733 (unless there is another generation with the name Passco that we don’t know about), which means that if Tabitha was born in 1755, he was 22 years older than her. However, if she was born in 1745, there was only 12 years difference in age. Since such age differences were not uncommon, does this age difference have any meaning?

What is important is that if Tabitha was born in 1745, John Adams wouldn’t have been her father as he was only 10. He wouldn’t have likely fathered a child until he was 13 or more likely 15. This would mean that for Tabitha to have been his daughter, she would have to have been born between 1748 and 1755 inclusive, but was she?

Who Would Have Known?

The story was shared at least within two family lines that descend from Passco and Tabitha’s son William. It is important to note that they were co-located and were in Indiana, but were far from where Tabitha’s family or people who raised her lived. It is said that Tabitha moved with William’s brother John to Indiana. If so, she would have lived in the same area. So, there would have been an opportunity to learn of Tabitha’s beginnings from her. However, the question in my mind is, “How did she know?”

If adopted or raised by some family, would they really have known the story of Tabitha’s conception? In my experience helping adoptees, my guess would be that they would not have known and if they did, they likely would have kept it a secret or changed the story in some way.

If raised by her mother, her mother would have known and could have shared the information with Tabitha. But, would she had done so?

If Tabitha was born in Massachusetts or somewhere nearby and was sent away as a baby or young child, she couldn’t have possibly known who her parents were. Is it simply a story she made up?

DNA Evidence

Does DNA show a tie to John Adams? Using DNA to prove a connection to John Adams would be challenging. The number of generations required to make a connection and the fact that it is a common name add complexity. In my case, it is even more challenging since I am also related to the Adams that married into the Johnson family. Similarly, I am also related to at least one Smith family, which is also tied to the Johnson family. All of these families came together in Wayne County and Randolph County in Indiana. And, all of them had ties to North Carolina.

I have verified my Adams family line to Chester County, Pennsylvania in 1708. Additionally, I believe the family was in that area at least as early as 1690. My Adams family line appears to be a completely separate family line from President John Adams family. My family appears to have immigrated either to New York or Pennsylvania while John Adams’ family immigrated to Massachusetts.

A major DNA undertaking would likely be required to have any hope of proving this connection.

The Real Story

No matter what people put in their family trees, the real story may never be known. Too bad we can’t go back in time and find out exactly what happened. Until then, it will remain an interesting story, but won’t be listed in my tree as fact.

Image: By Gilbert Stuart – This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the National Gallery of Art. Please see the Gallery’s Open Access Policy., CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81314356

Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Interesting Stories

Births, Marriages, Deaths, and Interesting Stories

Hunting & Fishing Licenses

Hunting & Fishing Licenses

Hills Brother Lumber

Hills Brother Lumber Hiattville State Bank

Hiattville State Bank

Cars

Cars