This story starts with a Seaman’s Certificate and ends with orphans, “servants,” George Washington’s hair, and a body donated to science.

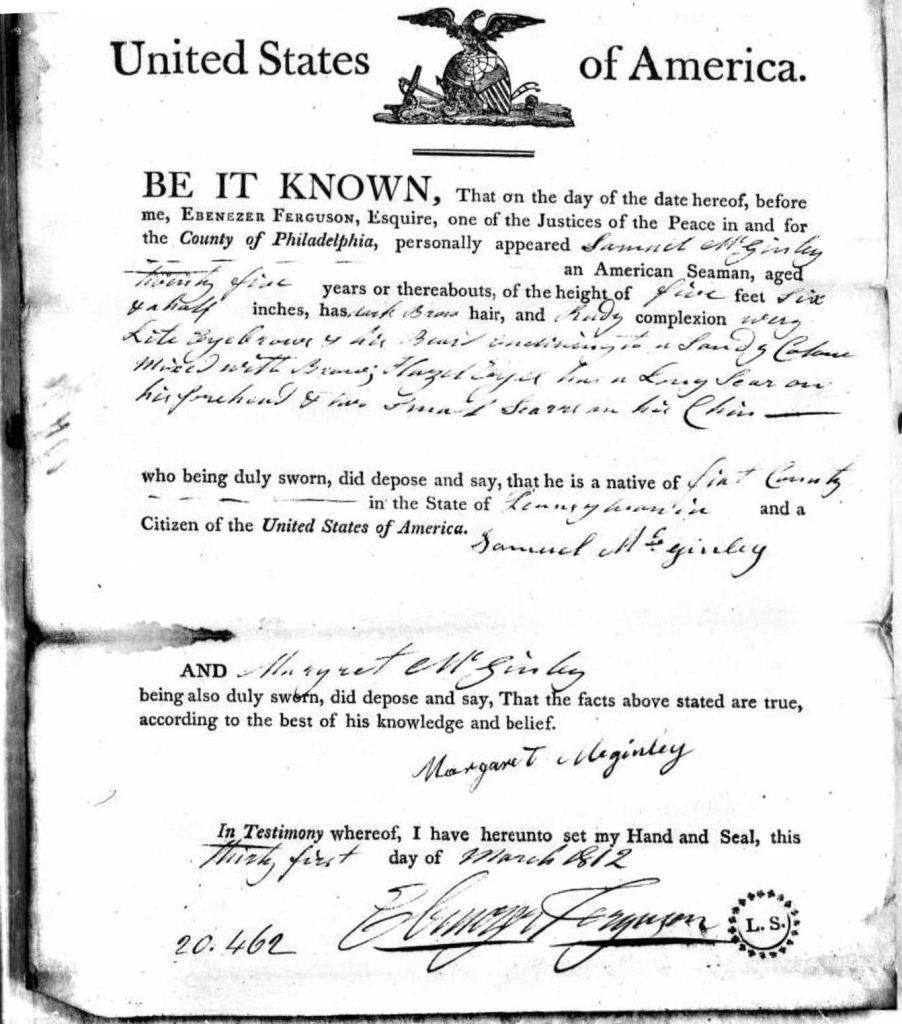

The Certificate

Some time back I discovered a Seaman’s Certificate for Samuel McGinley. It was signed by Margaret McGinley, which was odd as the certificate was clearly set up specifically for a man to sign. It was 1814 and women didn’t often sign legal documents. However, Samuel’s father Captain John McGinley, who served as superintendent of blacksmiths during the Revolutionary War had died ten years earlier. Thus, Margaret McGinley, nee’ Hurrie, certified her son as a U.S. citizen.

The U.S. Congress had passed an act in 1796 to create the protection certificates to protect merchant seaman from being pressed into service by the British. They had become very important during the War of 1812. Certification by a sworn statement was the most common proof used to get a Seaman’s Certificate. However, a birth certificate, naturalization papers, or other official record could also be used.

From this we can assume that Samuel traveled outside the coastal waters of the United States. However, nothing is known about his life on the sea.

The Marriage

The next record for Samuel is his marriage on February 23, 1814 to Jerusha McCann in Charleston, South Carolina. Jerusha was the widow of Edward McCann, who had died in 1809. Her maiden name is unknown.

Besides a wife, Samuel gained a step-daughter Mary Ann Louisa McCann. Mary Ann was not in the household long, as she married Samuel W. Wilcox just over four years later.

Edward’s will mentions no other children.

The 1820s

In 1822, Samuel was listed in The Directory and Stranger’s Guide, for the city of Charleston as a carpenter living at 74 Market Street. However, by 1824, it stated that his occupation was “boarding house.” It did not specify if he managed a boarding house or owned one. However, it listed him at the same address that he was living at in 1822. Neither of these jobs seemed aligned with his previous job on the sea.

1830s

In the 1830 census, Jerusha is listed as head of the household with a girl between 15 and 19 years of age living with her. The relationship to this girl is unknown and she doesn’t show up in any other records with Jerusha and Samuel. There were also three male slaves or servants, as Samuel referred to them, in the household.

Samuel was absent. Possibly he was traveling or working away from home. Five years later he is listed at 17 Price’s Alley. In that record, he is again listed as a carpenter. Thus, it isn’t exactly clear as to his occupation.

1840s

In 1840, Samuel and Jerusha are living in a household with two male slaves and two female slaves. The following year their son-in-law Samuel W. Wilcox, who was an accountant, died. Samuel petitioned to be the administrator of his estate, indicating that he was his son-in-law’s biggest creditor.

Travels

In 1845, Emma of Philadelphia came to visit Samuel. It is unclear who this woman was. No woman named Emma has been identified in Samuel’s family during that time period. However, during the 1840s Samuel took several trips to Philadelphia via boat. It is possible that Emma’s visit was in some way related to those trips.

Summer of 1849

Summer of 1849

In 1849, Samuel agreed to purchase Gibbes & William’s Mill from the city. However, soon after, he filed a request to be released from the agreement. He offered $100 in exchange for the release. He stated that unexpected difficulty had arisen and he would not be able to meet the requirements of the deal with the city. The city decided that the mill, which they described as at the west end of Tradd Street, should be sold as soon as possible.

It would seem most likely that the issue was one of money. Earlier that same summer, Samuel was one of several members of the grand Jury that requested pay for being on the jury. At the time, men selected for duty on the jury were compelled by law to serve up to three weeks, depending on the business of the court, without compensation. The group argued that other courts paid those who were required to serve.

Properties Associated

with Samuel McGinley

Charleston 1849. Source: https://www.sciway.net/hist/maps/mapscharleston.html

The map highlights approximate locations of properties associated with Samuel McGinley. In many cases, the exact address has not yet been identified.

Pink – Locations that Samuel owned, advertised, or said that he was located.

Green – It marks Broad Street as Samuel requested that an unplanked portion be planked.

Orange – Orphanage

Note: There are two pink indicators that have a “?” on them. This is because there are two different Bull Streets and the reference to that street did not have a specific address. Thus, I marked both areas.

1850s

In 1850, Samuel was 64 and his wife Jerusha was 71. By this time, Samuel had accumulated $1200 in real estate and his wife owned $3600 of real estate. It is assumed that she inherited these properties from her earlier husband Edward McCann.

James Hynes, a boatman of Scotland, and his family were living with Samuel and Jerusha in their home on Price’s Alley. They also had four female slaves ranging in age from 38 to 65 and seven male slaves ranging from 8 to 64.

Jerusha’s Death

Two years later, Jerusha died, leaving her entire estate to Samuel. Although no record of her daughter Mary Ann Louisa (McCann) Wilcox’s death has been found, it is assumed that she must have died by 1842, as that was the date of Jerusha’s will. Otherwise, one would expect her to have received something in her mother’s will.

Trips To Philadelphia

During this decade Samuel continued to make trips to Philadelphia with at least one trip to New York. Sometimes he traveled on steam ships, such as, the Osprey, Columbus, and James Adger. Other times it was a brig, such as, the Cohansey and Paul T. Jones. However, sometimes he traveled on schooners like the Somers, Constitution, and Dart.

Upon My Death

Dying in 1857, Samuel did not live to see another decade arrive. He had no descendants. However, he had a very detailed will that ensured his wishes would be followed.

To Family & Friends

Samuel made some traditional monetary distributions to a few of his family members. To his sister Mary (McGinley) Davis, a widow, he gave two hundred dollars per year for the rest of her life. He gave the same amount to his niece, Maria M. (Owens) Lyons, daughter of his sister Martha. Maria was also a widow. Oddly, he did not give money to Martha, who was also a widow.

To his friend John Dougherty, he willed $200. Interestingly, he was listed in John Dougherty’s will with the same amount of distribution.

Washington’s Hair

The only personal possession that he willed to anyone was his gold ring with George Washington’s hair in it. It is possible that it was one of the 22 rings designed for family and friends of George Washington. If so, it would have had an engraved image of President Washington on it. See https://artofmourning.com/george-washington-memorial-ring/ for an image and more information.

However, it is more likely it was a ring fashioned by someone else as numerous people appeared to have had rings made that supposedly contained Washington’s hair. It seems that in his position as a general and first President of the country, memorials of George were in high demand, even when he was still alive. Relatives, colleagues, members of the military, and others desired to have something related to Washington. In many cases, hair was requested. See https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/george-washington-hair-relics/ for more information.

In either case, the question arises of where Samuel would have gotten Washington’s hair or the ring after it was made. One possibility is that his father Captain John McGinley, who was the superintendent of blacksmiths during the Revolutionary War, had received the ring or the hair. No mention of it is made in his will. However, he gave his entire estate to his wife Margaret (Hurrie) McGinley.

It is possible that he inherited it from his wife. Perhaps Jerusha’s family or her earlier husband Edward McCann’s family had some association with George Washington. Another possibility is that he somehow obtained it from the local orphanage as George Washington had laid the cornerstone for the building of the first permanent orphanage in the new country. That occurred on November 12, 1792, before Samuel was in the area. However, Samuel did have some connection to the orphanage.

McGinley Education Fund

Samuel ordered the rest of his estate, including eight properties, shares of stock in two banks, his remaining slaves, and his personal items to be sold. The money remaining after accounting for the money willed to family and friends and paying any debts was to be used to create the McGinley Education Fund. Additionally, after his sister and niece died, the money set aside to create an income for them was to be added to the education fund. Additionally, he stated that he had or was planning to apply for his father’s military pay from his Revolutionary War service.

The trustees of the fund were to be the mayor of Charleston, the city treasurer, and the chairman of commissioners of the Orphan House of Charleston. The trustee role was assigned to the position rather than to the people currently serving in those positions. Thus, for example, when the city elected a new mayor, the new mayor would replace the outgoing mayor on the board of trustees.

The income from the fund was to be used for the education of “orphan children of deceased members of the St. Andrews Lodge of Masons.” The other requirement was that the children must have been born in the country. The children sponsored would be nominated by the master and wardens of the lodge. If there is a surplus of income it was to provide for education of orphans of other masons.

Caring For Elderly Servants

Samuel bequeathed his servants (slaves) Flora and Mary, who were elderly, to John Dunn. John worked for Samuel and lived in his home. He was also designated as Samuel’s executor. Samuel did not feel that Flora and Mary could provide significant value to anyone and he wanted them treated humanely. Thus, he gave John $200 ($100 each) per year to care and provide for them. The amount was to be cut in half upon the death of either of them. The yearly amounts expired upon the death of both servants.

Body to Science

Lastly, Samuel ordered that his body be given to Doctor Henry William Desausser. He wanted the doctor to look specifically at the bones in his chest. He had experienced what he called “complicated diseases” during his life and he wanted to see if understanding his body could lead to help for others who might experience similar issues. Nothing is known about the physical ailments that Samuel experienced except that he died of stomach cancer.

He also wanted his body to “be skeletonized.” And, he stated that this should be done without a cost to his estate.

Afterward

Samuel has so much more to his story. The story of his ownership of “servants” is one path that needs further exploration. His relationship with his various friends and acquaintances would be very interesting to understand. Additionally, research of the properties that he owned could be quite interesting. They were all over the city as shown on the map. At least one was leased and not all had buildings on them. Why did he make a significant number of trips to Philadelphia? And, why did he want to buy a saw mill?

Featured Image Source: pixabay.com

Summer of 1849

Summer of 1849