Usually, papers being lost means a loss of information. However, in the case of William Bassett, my 4th great-grandfather, the loss of his papers stating that he had served in the Revolutionary War led to great insight into his service in the Continental Army.

Pension

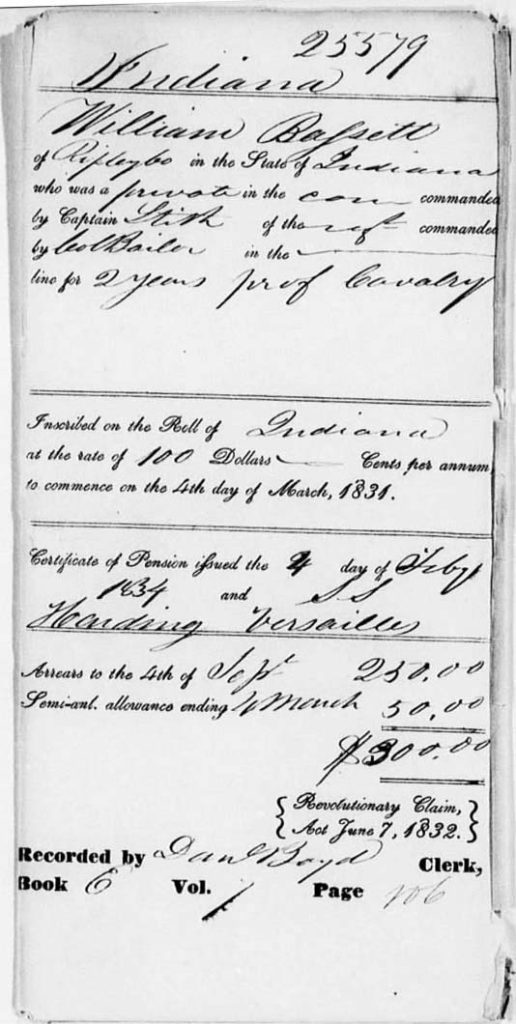

On June 7, 1832, the U.S. Congress passed legislation that provided a pension for all men who served at least two years in the Revolutionary War in the Continental Line (official army raised by the Second Continental Congress), state militias, and other formal military groups. The act provided for benefits retroactive to March 4, 1831.

It wasn’t until December 29, 1833 that William Bassett appeared before Judge Joseph Robinson of the Ripley County Circuit Court and made a “Declaration for a Pension.” At the time, William was 79 years of age and was physically ailing. The document claimed that due to his infirm condition that he was not able to make his statements in an open court. Additionally, William was not able to write a statement himself as he was illiterate.

William’s claim, in brief, was that he had served in the Continental Army for 2 years and 9 months and that his papers regarding his service had been burnt when the Indians burned Craig’s Station in Kentucky.

In his file, along with William’s sworn statement, were a sworn statement from his wife Peggy, answers to “The 7 Questions” (assumed to be questions required to be answered by the pension office), and various correspondence with pension authorities. William’s pension file, which is over 50 pages long, provides a glimpse into William’s life.

Early Life

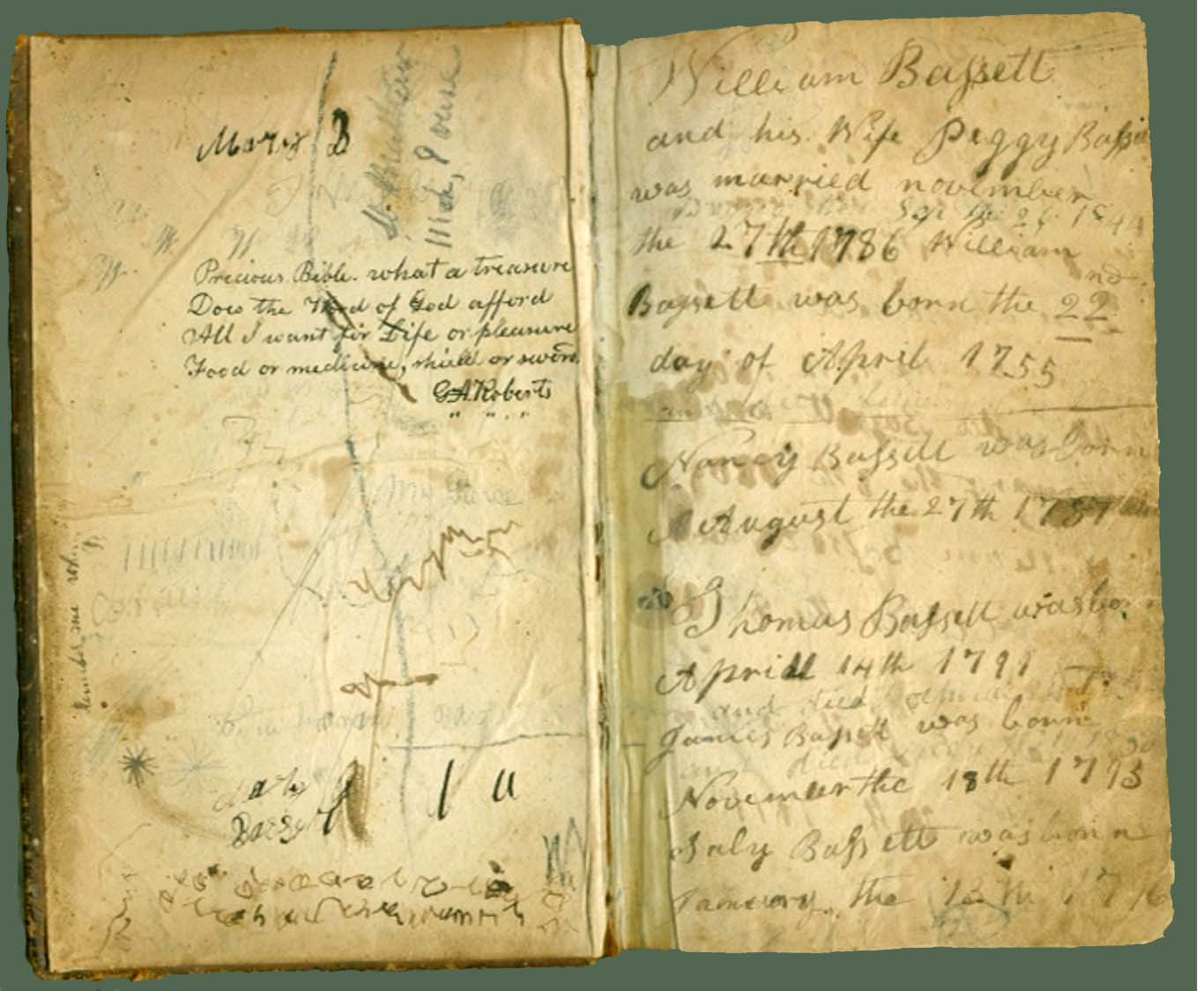

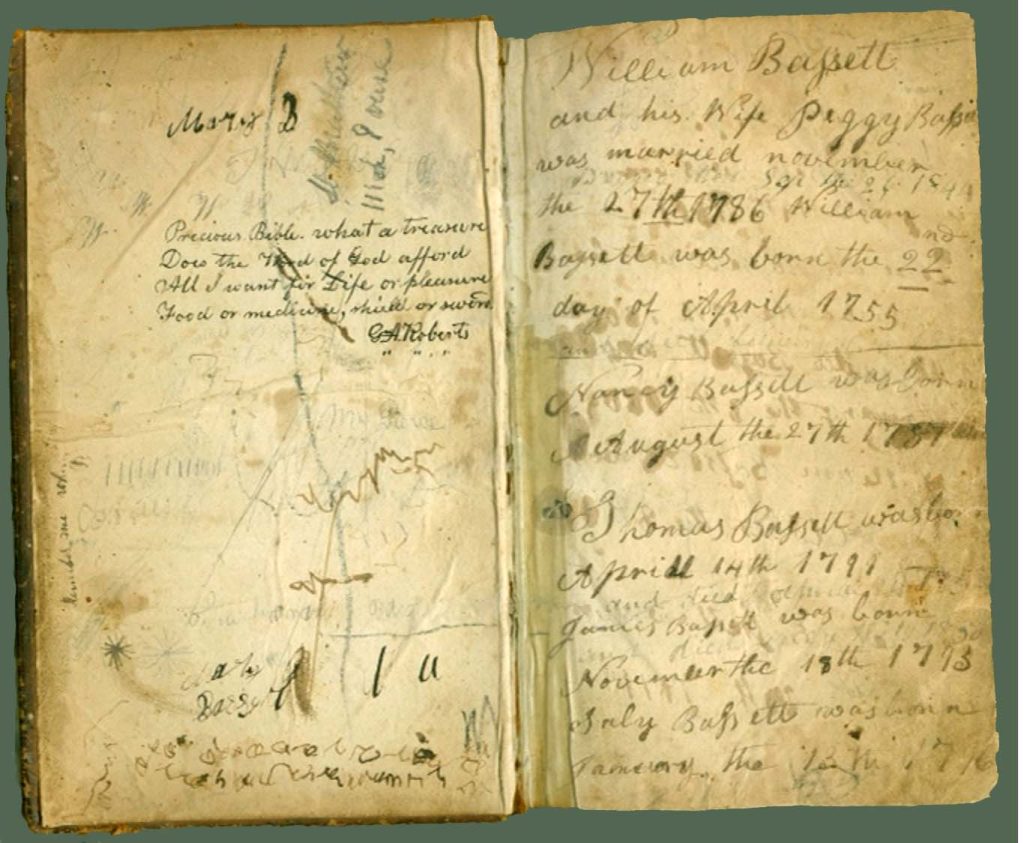

According to his military record, William Bassett was born April 18, 1755 in Limpsfield, Surrey, England. Neither the family Bible nor his military pension files list his parents. However, it is possible that William is the son of Michel Baset. Michel baptized a son William in at St. Peters Church (Church of England) in Limpsfield on May 18, 1755 – one month to the day after William was born.

Arrival In America

The date William arrived in America is not answered in his military records or in his family Bible. There is, however, a record of British Deportees to America that indicates that a William Bassett was sent to the colonies in 1766-1767. It is unclear if this is the same William or a different one. If it is the same person, he would have only been about 12 years of age when he was sent across the ocean as a punishment for some crime that he supposedly committed. According to the laws of that time, a person could be sent to America for a wide variety of offenses from minor to serious. More research is needed to determine if this is the same William.

Revolutionary War Service

William was living in Botetourt County, Virginia in August 1776 when he enlisted as a private in the Virginia Military. He would serve in Captain John Stith’s Company. The company became a part of George Washington’s 3rd Continental Light Dragoon Regiment under the leadership of Colonel George Baylor.

William left with the unit for Fredericksburg, Virginia. He was at this location for approximately one year. Then he was on the move again going to Winchester, Virginia; Princeton, New Jersey; and Frederickstown, Maryland.

Smallpox Vaccine

George Washington, who had had smallpox and recovered, was desperately looking to contain the disease as it was running rampant through the American troops and impacting their ability to make progress against the British. He believed that vaccinating the soldiers for smallpox was a must given that the Army had not been able to keep it from spreading. Initially, he called new recruits to be inoculated, but found that wasn’t sufficient. Eventually, he decided that all the troops must be inoculated.

Thus, at Frederickstown, William, along with many other troops, were inoculated for smallpox. The process was risky, as a simple vaccine wasn’t yet available. Soldiers had to be inoculated using a process called variolation. With this process, live virus was introduced into cuts or scratches in hopes of inducing a mild form of smallpox. Then the soldiers had to spend time allowing the disease to run its course. The hope was that once the soldiers recovered that they would be immune to getting smallpox again.

The program, performed under extreme secrecy to keep the British from taking advantage of the recovering soldiers, was successful. It allowed William and the other soldiers to fight the British unhampered by smallpox.

On The Move

After healing from the inoculation, William and his unit headed to Redding, Pennsylvania. In pursuit of the British, the men ended up in Trenton, New Jersey. He wintered at the Wallace Edifice in Princeton, New Jersey. In the spring they had headed to Amboy and then to near New York City. When the British headed for Philadelphia, William and his unit moved to White Plains.

During the battle of White Plains, William was on the bank of the Delaware River. From there, his unit moved to Trenton, Brunswick, Springfield, Amboy, Elizabethtown, Morristown, and finally back to Trenton. After the battles of Trenton and Princeton, William’s unit hunkered down for the winter.

Monmouth Courthouse

William Bassett remained at Trenton until the following spring. It was then that he moved to near the Monmouth Courthouse. During the battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778, William and eleven other members of his company served with the guard of General (Charles) Lee.

That day General Lee, second in command in the Continental Army, led an initial assault on the British that did not go well. When Washington arrived, words were exchanged between the two, although the extent and severity seem to be up for debate. Soon additional troops arrived and the battle continued throughout the day. During the cover of darkness the following night, the British withdrew to New York City.

Baylor’s Massacre (Old Tappan)

The Set Up

William reported that after the Battle at Monmouth, he had went to Hackensack for a period of time before moving on to Old Tappan, where he was stationed in a stone barn. According to William, the “men were quartered at Tappan and the inhabitants of the place pretended to be very friendly to the cause of the Americans, and some of them made parties for the American soldiers and furnished large quantities of spirits of the choicest kind for the troops – and the American soldiers supposing themselves safe and in the homes of their friends became merry …. In the meantime the Torys sent off runners to New York to inform the British of the situation of the troops.”

By this time, William was asleep in a stone barn with many other men. Other troops were quartered in various houses and buildings in the area. However, at that moment, most of the men were not in a situation to defend themselves even if they knew that they were in danger “owing to the carousal a few hours previous.”

The Attack

William “was aroused from his sleep by the breaking of doors without and the cries of the soldiers for quarter – two men were sleeping close to him – the same corner and he attempted to awake them for he knew that the troops were surprised by the enemy – but he could not succeed in arousing any of the men, being insensible through drinking, and therefore proceeded to make his escape and run to the large door and slipped (out) a sliding door (which was contained in the large door) but notwithstanding the darkness he could see plainly the barn was surrounded by armed men, he therefore asked for quarter, They replied to him “goddamn your Rebbel soul we will give you quarter” and they demanded of him “how many men are in the barn” – he answered that he did not know how many. At this time the men within had become alarmed except those who were drunk, and were running out to the various places in the barn where they could make their escape, whereupon the British and Tory’s cried out “Skiner them – Skiner them” (which meant bayonet them).”

Prisoner of War

The British took William prisoner. He was “ ordered to stand while an armed man stood by to guard him.” When the guard was some distance away, he “sprang over a fence to escape.” As he “was jumping over the fence, he was stabbed in the back by a plunge of his pursuer’s bayonet which entered near the backbone,” wounding him significantly. However, despite almost fainting from the pain, he managed to escape the grasp of the enemy.

According to William, all the men, who were stationed with him, were either killed, wounded or taken prisoners except Captain Stith and seven other men. He recalled the “cries and groans of the wounded and dying.” And, further stated that “[t]he horrors of that night will never be effaced from his memory.”

Discharge

After escaping, William moved to Trenton, New Jersey before continuing on to Philadelphia. He remained there until spring when he went to Baltimore. William received an honorable discharge at Baltimore in May 1779. It was upon his discharge that Captain John Stith gave him papers certifying his service. Those papers were later burnt when the Indians burnt Craig’s Station in Kentucky.

In his description of his service, William stated that during his service, he had been acquainted with (I assume that means “knew of”) generals Washington, Greene, Gates, Lee, Paulaski, Maxfield, Purnam, and Wayne. He also knew colonels Spencer and Washington, along with many others. However, he could not remember all the units and militia groups that he had encountered.

Life After The Revolution

The Frontier

William moved to Kentucky after his service in the revolution. It is believed that William ventured to Kentucky with Daniel Boone and a group of Baptists in about 1780. He is said to have been with Boone on numerous occasions. (William’s adventures with Daniel Boone are a story for another day.)

Marriage

It wasn’t until November 22, 1786 that Mary McQuiddy gave her consent for William to marry her daughter Margaret “Peggy,” who was about 17 or 18 years of age. On the same day, John McQuiddy (likely Peggy’s brother John) and William Bassett entered into a marriage bond in the amount of fifty pounds of current money. They were married in Mercer County, Kentucky on November 27, 1786 by Rev. Rice.

Their Offspring

William and Peggy raised 10 children. No question exists as to the parentage of 9 of the 10. However, the parents of their oldest daughter, Nancy, are unclear.

The family Bible records Nancy’s birth as 1787, the year after William and Peggy married. However, it is believed that her name was Nancy Roe, she was born at an earlier date, and that she was an orphan. However, it does not appear that anyone has been able to confirm her parents names or the specific circumstances of their death.

Indiana Bound

Indiana Bound

In June 1817, William purchased land in Ripley County, Indiana, which had just opened up for settlement. In November of the following year, William sold 300 acres of land in Franklin County, Kentucky. The family moved to near Cross Plains, Brown Township, Ripley County, Indiana.

Many families from Kentucky moved to this area about this same time, including the Ellis family, who would marry a descendant of William and Peggy.

In 1821, the Middle Fork of Indiana Kentucky Baptist Church was founded. William Bassett was one of the deacons. And, the land was donated for the church by James and Mary Benham (Roger Ellis’ daughter and her husband).

The Pension

In 1834, after providing a detailed statement about his service and answers to the required questions, William was allowed a pension of $100 per year with it paid semi-annually.

Then in 1838, William made his will. He gave each of his children, whom he did not state by name, the sum of $1 each. The remainder of his estate was to go to his wife. Upon her death or if she was not living, the remainder was to be divided amongst his children. He made no provision for the families of any children that might not be living.

William died February 6, 1840. Peggy was allowed a pension after his death. Four years later on September 26, 1844 Peggy died. William and Peggy are buried together on the family farm ½ mile west of Cross Plains in Ripley County, Indiana (denoted on find-a-grave as “Bassett Cemetery”).

Notes

We descend through William and Peggy’s daughter Sarah. The entry for her in the Bible is at the bottom of the right page.

The term “Indians” is used rather than the current term of “Native Americans” to allow the article to be more consistent with the accounts of William Bassett and the terminology of that era.

Indiana Bound

Indiana Bound