How does Henry Thomas, a Missouri farmer and brick mason, decide to leave his home and family to join Colonel Gentry’s regiment to fight the Seminoles in the Indian Wars in Florida?

Was it for the money? This is doubtful as the Missouri men were offered $8.00 per month plus 40 cents per day per horse, which was less than friendly Indians were offered to join the fight. Was it for the prestige of being a soldier? Possibly. Was it for the camaraderie with his neighbors and friends? Also, possible. But, most likely, it was for the adventure.

North Carolina

Henry Thomas, my 3rd great-grandfather, was born March 31, 1814 in Caswell County, North Carolina. He was the son of Josiah and Ruth (Mitchell) Thomas. Around 1830, his family, including his grown siblings, moved to Ralls County, Missouri. It was claimed that the reason for the move was that they had too many relatives in North Carolina. Of course, that didn’t stop them from creating a huge family presence in Missouri.

Request For Troops

The “Problem”

Conflicts were occurring in Florida between the settlers and the Native Americans. At that time, the Native Americans were referred to as Indians. Thus, this article will reference them as such for authenticity.

The U.S. government decided the best solution was to relocate Native Americans. Despite the Indian Removal Act and an agreement to move, the Native Americans refused to vacate the area. They hid in the swamps and made themselves difficult to find. Yet, skirmishes and outright battles followed. When conflicts continued, Missourians got in the act.

Request to Missouri

In September 1837, the government decided to ask for more men to get this dispute settled. Senator Thomas H. Benton from Missouri was very vocal about the need for frontiersman to remove the Native Americans. He didn’t believe it fit the typical Army role and he felt that frontiersman were much more suited to address the issue.

Senator Benton then convinced President Van Buren to allow volunteers from “frontier” states to join the effort in Florida. After passage of the legislation, the Secretary of War requested the governor of Missouri to put together a regiment of men to go to Florida and assist in the removal of the Native Americans.

At the senator’s request, Richard Gentry, a personal friend of Senator Benton, was appointed to lead the regiment. Richard Gentry, a son of a Revolutionary War veteran, was the General Major of the Missouri Volunteers during the Black Hawk War of 1812. Thus, he had direct experience fighting Indians. In addition, he had significant other military experience. He was also a well-known significant person in Columbia, Missouri, where he had been a founder, mayor, postmaster, and owner of a hotel/tavern. Richard Gentry accepted the role and was was commissioned as a colonel with the directive to have a regiment of 600 men ready to serve within a couple months.

Raising A Regiment

Richard Gentry set out immediately to gather men to fight in Florida. To do this he traveled throughout several Missouri counties to find recruits. He obtained recruits from Boone, Callaway, Howard, Chariton, Ray, Jackson, and Marion counties. The recruits from each county were led by a captain, except Callaway County, which had enough men to require two companies and two captains.

One of the men that agreed to join the unit was Henry Thomas, my 3rd great grandfather. It is unclear which company he joined as it appears his family was living in Monroe County, which didn’t raise a separate company. However, multiple counties nearby raised companies to join Gentry’s regiment.

Henry’s motivation for volunteering is unknown. It could have been that he felt it was his duty or that the pay was considered good in a time of economic turn down. On the other hand, it might simply have been for the adventure of seeing more of the country or because he had friends who were going to serve. As far as I know, none of his brothers joined the unit.

Money For Supplies

Twenty-three and unmarried, Henry was likely still living at home. As such, it is most likely that the horse(s) he used belonged to his father. This posed a problem for many of the young men as they were to be a mounted unit. And, they were required to bring their own horses.

Despite wanting to join the regiment, many simply couldn’t afford to purchase a horse. Colonel Gentry helped them out by endorsing notes for them so that they could purchase horses. The notes were due in seven months, which made for a tight timeline to go to Florida, fight, and return before they had to be paid.

The Send Off

On October 15, 1837, friends and neighbors gathered near Gentry’s Tavern to see the men off and wish them well. The well-attended event was full of speeches and cheers from the crowd. The teacher at a local academy presented the unit with a flag that the girls had made. Meanwhile the girls made a patriotic statement by wearing red, white, and blue attire.

Before the regiment and their Indian scouts marched away, a good friend of Gentry expressed his concern for Gentry. He said, “I fear this will be our last interview; I know you are a brave man, but there is also an element of rashness in you. If you are ever in battle, you will lead the charge and be killed!”

As the regiment headed for their first destination, St. Louis, the colonel’s young son, mounted his father’s horse and rode with him until the regiment stopped a mile east of Columbia to water their horse. He then dismounted and waved good-bye to his father.

Florida Bound

The St. Louis Stop

It took the men five days to cross the 125 miles separating Columbia from Jefferson Barracks, south of St. Louis. There, the men were given weapons. Five of the men in Gentry’s regiment are said to have hit a 2 inch square at 140 yards. It was surmised that the volunteers might be better marksmen than the Army regulars as it was claimed that some among them could hit a white-tailed deer that was on the run.

While in St. Louis, Major General Gaines reviewed the regiment. Then, just before the men continued their journey, Senator Benton arrived from Washington D.C. to speak to the enthusiastic, excited group. And, Col. Gentry said that he had been reassured that the regiment would be paid in gold and silver. The speeches “concluded by wishing that each man might gain honor as a soldier and return in health.”

New Orleans By Steamboat

The men left St. Louis on October 25, 1837. They sailed down the Mississippi River on the steamboats United States and St. Louis. The trip took 6 days.

The men didn’t want to spend any more time in New Orleans than required as the city was in the midst of a yellow fever epidemic. People were dying faster than they could be buried. Everyone was terrified and over 150 men simply left and went home.

Florida By Sailing Ships

By the time the men sailed for Florida on November 3, the 600-man regiment numbered only 432. The trip was uneventful and they reached Tampa Bay 5 days later.

The horses were sent to Florida on smaller ships. However, they didn’t leave until a few days after the majority of the men sailed. The horses were placed on the boats by men who did not understand the impact of a large body of water on a small boat. As such, the horses were not properly secured on the boat. To make matters worse, a terrible storm came up. The ships rolled and the horses fell about. Horses were injured and killed. Others starved as storms caused the journey to take three weeks instead of five days.

Only 150 of 450 horses were healthy after the trip to Tampa Bay. Since the regiment was to be mounted, all the men whose horses died were discharged or forced to walk. The men that were discharged had to make their way home on their own. They were not paid in gold and silver. The discharged men also were given only half of the promised daily allowance for their horse. Thus, the men lost money and were very disgusted with their treatment.

Since Henry continued with Gentry’s regiment, his horse was clearly one that survived, as nearly all of the men without horses left for the Midwest.

Florida

Second Class Soldiers

At Fort Brooke, Col. Gentry and the remaining members of the Missouri Volunteers joined the First, Fourth, and Sixth Infantry, creating a brigade of nearly 1,000 men. Col. Zachary Taylor was the commanding officer. He was a regular Army man and resented that he had to be burdened with the volunteers from Missouri. Thus, from day one they were made to feel second class. Not only did the colonel treat them that way, but so did the Army soldiers.

Then, before the men left Fort Brooke near Tampa Bay to push into the interior of Florida, tragedy again struck Gentry’s regiment. The men were guarding 80 wagons of supplies that were headed to Ft. Fraser, a new supply depot on the Peace River when Col. Gentry’s son, who was also serving, accidentally discharged his weapon and killed a private in the regiment.

Before the regiment had gone far, a portion of the Gentry’s men, who were walking because they had lost their horses, demanded to be discharged. It was granted and they left for home. At this point, Gentry’s regiment had dwindled to four companies with only a quarter of the 600 men that left Columbia, Missouri with Gentry.

The men’s departure just reinforced the regular Army’s view of Gentry’s unit. When there was a difficult task to be done, anything risky, or just downright unpleasant, Col. Taylor would assign it to the volunteers. That included having them be the advance guard, keeping ahead of the main body to protect the regular Army. They also got the chore of building roads where needed to allow passage of the heavy baggage. One Officer stated, “[The colonel] used the Missouri Volunteers more like [black men] than anything else I can mention.”

Over Land and Through Swamps

As the men moved southward, they encountered various groups of Indians, sometimes with African Americans amongst them. They took some individuals prisoner and relied on friendly Indians to assist in navigating and obtaining information about the movement of the Seminoles. They also sent out spies to separately look for the Seminoles and see where large groups of them might exist.

Many leads were simply misinformation. Other times, it seems the Indians had gotten wind of their plans. For instance, one time the soldiers reached a large Seminole camp only to find it deserted. The men thought that several hundred Indians had camped in the location and had left very quickly. Fires were still burning in the camp and meat was still waiting to be consumed. New leads led to another hammock about a mile away.

Finally, the opportunity that Col. Taylor sought to defeat a large group of Indians in a major attack presented itself. Scouts learned that an estimated 2,000 Seminoles were gathered on the shore of Lake Okeechobee.

By this time, Col. Taylor’s men, including Col. Gentry’s Missouri Volunteers had traveled 150 miles, taken about 150 people prisoner, created supply depots, built forts, opened roads, built bridges, and made causeways. But, the big battle was yet to come.

The Battle of Okeechobee

Col. Taylor learned that an estimated 400 Seminole Indian warriors were held up in a hammock in Lake Okeechobee, along with leaders Billy Bowlegs, Alligator, and Wild Cat. This would be where Col. Taylor attacked.

Strategy Disagreement

Col. Taylor called together the officers to discuss the attack strategy. Col. Taylor preferred a frontal attack strategy. Meanwhile, Col. Gentry strongly recommended going around the swamp and attacking the flank with a strategy to encircle the Indians. He argued that slogging through the swamp would exhaust the men.

Taylor, however, wouldn’t listen to a word Col. Gentry had to say. Instead, he accused Gentry of being afraid of a direct attack. He had decided; it would be a frontal assault.

Col. Gentry disagreed, but felt that he had to follow Col. Taylor’s orders since he was the commanding officer.

The Attack

On Christmas Day 1837 under the mid-day sun, the brigade moved into position. 132 Missouri volunteers and members of Morgan’s spies made up the first line. The 4th and 6th infantries followed them and the 1st infantry was in reserve. At the appointed time, Col. Gentry, who was to lead the way, pulled off his coat, rolled up his sleeves, and yelled, “Come on, my boys.”

The Approach

The approach to the hammock was a treacherous one. It was like a natural fortress with a natural moat. The men left their horses behind and trudged through the swamp. For a half-mile, men had to wade through deep, muddy swamp water making their way through 5-foot-high saw-grass to reach it. The men had to hold their weapons and gun powder in the air to avoid them getting wet. Additionally, the saw-grass was given that name for a reason. It tore skin and clothes like they were butter.

When the men moved within range of the Indians, heavy fire erupted.

The Defense

The Indians had selected their position very carefully. They hid themselves in a hammock, a raised area in the swamp that was thickly covered with trees, bushes, and vines. The hammock backed to Lake Okeechobee. The Indians had also spent a great deal of time cutting down the grass and other cover for several feet in front of the hammock forcing the men to be in the open if they attempted to reach the hammock.

The position gave the Indians the upper hand. They were well prepared, even having made notches in trees to hold the barrels of their guns. The Indians could peek out and see the troops coming toward them. Meanwhile, their scouts climbed high in the trees and could see the entire field. All the while, the Indians remained well hidden.

In case an evacuation was needed, the Indians had placed canoes on the far side of the hammock at the edge of Lake Okeechobee. They had a thorough strategy.

The Fight

The Missouri Volunteers were to retreat behind the regular Army. However, the Missouri volunteers moved toward the hammock. Being on foot, they could not move quickly. And, the way they had been treated, it may have been that they thought they had something to prove. Gentry’s men kept fighting, but heavy casualties could not be avoided.

Gentry Hit

Col. Gentry’s white shirt made him an easy target and he was hit multiple times. Despite his wounds, Col. Gentry continued to encourage the men to fight. After about an hour, he finally fell to the ground at the edge of the hammock. While the fighting was still going on, Henry and another man (or men) placed Col. Gentry in a blanket and carried him a half-mile through the swamp back to the Army’s hospital.

Fighting in the saw-grass was challenging at best and deadly to many. The Missouri Volunteers had to duck volleys from the regular Army as well as the Indians. They ducked down in the grass and sometimes even ducked under water. They were basically sitting ducks in the middle of a fire fight. Then when a man was injured, they had to get him to shallow water or onto land so that he did not drown.

As the fighting continued, it was a bit of a step forward followed by a step backward. Actual progress was difficult to achieve. Since the Indians held the upper hand, the men were forced to fight in the style determined by the Indians. This meant that the battle became a series of skirmishes.

Indians Escape

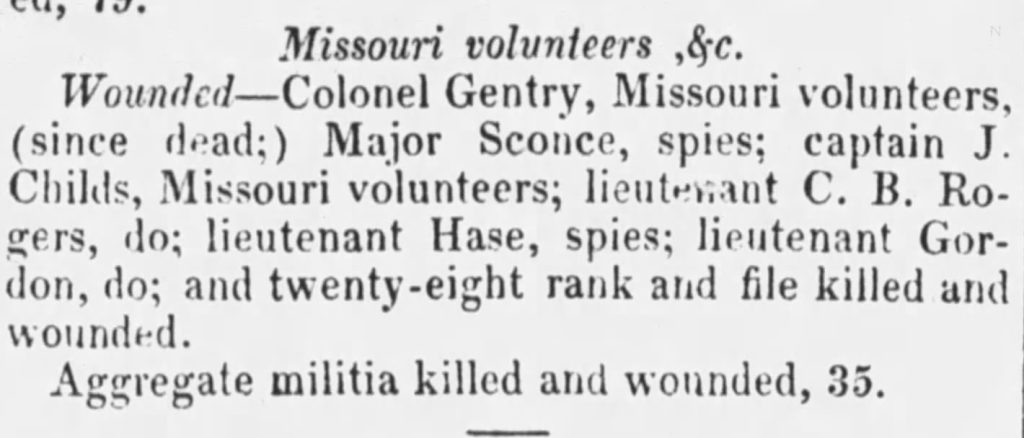

When the fighting was over some three hours later, the Indians had managed to evacuate the encampment. Thus, the prisoners were few. However, every officer but one in the 6th Infantry was killed with many others in the unit killed or wounded. The high casualty rate appears to have occurred because the men were very close together. One company in particular was hit hard as only four members of the company were unharmed in the battle.

The Missouri Volunteers had a 25% loss in terms of killed and wounded. In total 26 or 27 of Taylor’s men were killed with another well over 100 wounded. The Indians left 10 bodies behind, but it was assumed that more had died and that the Indians had taken their bodies from the scene.

Col. Gentry’s Death

When the battle concluded, the men made a footway across the swamp. After it was complete, all the dead and wounded except one who was not found were carried on litters out of the swamp.

In the meantime, doctors tended to Col. Gentry’s wounds. They decided to clean the wound, which entailed putting a handkerchief on a ramrod and pushing it through the opening in his abdominal area all the way through the other opening in his back. This did not improve his condition. Instead, he quickly worsened.

Col. Gentry called for Col. Taylor and it was reported that the following conversation took place:

“Gentry: Colonel Taylor, I am about to die. I depend on you to do my brave men full justice in your official report.

Taylor: Colonel Gentry, you have fought bravely; you and your men have done your duty and more, too! I shall do them full justice, you may be sure.”

Col. Richard Gentry died just before midnight. His son, who had been seriously injured, and other men in the Missouri Volunteers were with him in his last moments. Col. Gentry and the others who had died were buried the following morning.

Return to Tampa Bay

After the battle, the men returned to camp. They spent the following day interring the dead, stabilizing the wounded, making more litters to transport the wounded, and collecting the horses and cattle, which had been abandoned by the Indians.

The following day, the troops moved out. But, instead of driving further through the Everglades, the men headed back to Tampa Bay. With so many officers and troops killed and wounded, Col. Taylor really had no choice, but to end his Florida campaign. Therefore, the survivors, weary and tired, headed out of the swamps on December 27. They first headed to Kissimmee, where some baggage had been left. Then, they made their way back to Tampa Bay.

Two Tales Of The Same Battle

Taylor’s Report

Col. Taylor made his report based on discussions with the officers in the regular Army. He did not, however, get any input from the volunteers. His report stated that “Col. Gentry died a few hours after the battle, much regretted by the army, and will be doubtless by all who knew him, as his state did not contain a braver man or a better citizen”. However, that was the limit of positive statements about the men from Missouri. According to him, all the praise was due the regular Army and that the volunteers had fell back and refused to rejoin the fight.

The report resulted in a heated response. Secretary of War Poinsett, for example, defended the unit saying, “the heavy loss they sustained in killed and wounded affords sufficient proof of the firmness with which they advanced upon an enemy under a galling fire.” Although Col. Taylor did not change his report, his words when the volunteers were discharged were much more complimentary.

The Rebuttal

When they finally saw the report, the members of the Missouri Volunteers were disgusted and thought the report was an injustice and insult. They felt they needed to speak up, especially for those who could no longer defend themselves. They stated that they had experienced “extreme fatigue and hardship” on the march. At each point, Gentry’s unit was the first to penetrate and pass a swamp or hammock, protecting the main body of the Army. And, when they camped, Gentry’s unit was located in the most exposed and dangerous ground of the camp.

Misconception?

Of Taylor’s story of them not falling in like they should . . . the officers said, “Strange and unaccountable misconception – or yet more wonderful and willful misrepresentation!”

Taylor’s words upon their discharge did not change the sentiment among the Missouri volunteers that they had been wronged by Taylor and his report. The Missouri general assembly launched an investigation. The result was that they believed Taylor had not only made a false report that slandered the Missouri volunteers, but that he had done so deliberately. They requested the governor lodge an official complaint arguing that Taylor should not be an Army officer.

They acknowledged that a few may have quit the action, but most continued the fight throughout. When the Indians finally took off, the men from Missouri cared for the wounded and collected the dead. One officer said that he was not in the Battle of Okeechobee as he was ill. He went on to state that the Missouri Volunteers were brave (“as brave as any that ever lived”). And, he supported the report on the treatment of the men by the Army regulars. He noted that half of his men were casualties with one being killed.

To learn more about the Missouri Volunteers in this battle, read Missouri Volunteers at the Battle of Okeechobee: Christmas Day 1837 in the Florida Historical Quarterly Vol. 70, No. 2, Oct., 1991 available via jstor.

For yet another perspective of the battle, check out Christmas 1837: Seminole Survival and the Battle of Okeechobee .

the Aftermath

Zachary Taylor

The “war” was costly in terms of both money and life. Zachary Taylor led one portion of the fight, but that portion alone resulted in nearly 150 casualties. And, it wasn’t clear that a victory was achieved. In addition, if the complaint of the Missouri Volunteers was raised, it was clearly dismissed. Taylor went on to lead other battles and became the 12th President of the United States. He did not, however, win the state of Missouri!

Seminole Indians

The U.S. government and the Seminole Indians never did reach a peace treaty. However, a good portion of the Indians that survived the battles and skirmishes with the troops and volunteers eventually relocated to Indian Territory. By 1842, over 4,000 Seminole Indians were living in what became Oklahoma. However, some of the Native Americans remained in Florida by going deep into Big Cypress Swamp and the Everglades. The government did not pursue them.

When Chief Billy Bowlegs went to Washington D.C. in 1852, he stopped by Zachary Taylor’s photograph and said, “Me whip!” Today, several Indian reservations still exist in Florida.

Richard Gentry

Initially buried in Florida, Richard Gentry’s remains were sent to Missouri in 1839 to be re-interred at Jefferson Barracks. Along with his remains were the remains of other Army soldiers. The gravestone that was erected contained only the names of the Army soldiers. Col. Gentry was left out. However, Missouri legislature remembered him in 1841 when they named Gentry County in his honor.

In 1889, Gentry’s family learned that he was not included on the gravestone at Jefferson Barracks. The military would not change it, but allowed the family to add a gravestone for him at their expense. Later, a replacement stone was made listing Gentry and the other soldiers.

Ann Gentry

When Richard Gentry’s wife, Ann heard of his death, she said, “I’d rather be a brave man’s widow than a coward’s wife.” Ann was accustomed to managing the family’s nine children and the family’s businesses on her own. She had done so each time Richard had gone to serve his country. Now, Ann had to manage with even less. Not only was Richard not coming home, but all the notes that Richard had signed for the volunteers so that they could buy horses came due and his estate had to pay them. This left no money for Ann and the children. Thus, she had to continue to work.

Richard had been the postmaster of Columbia and Ann had filled in while he was gone. After he died, she was appointed the official postmistress becoming only the second woman in the United States to hold the position of postmistress. She served for 30 years, including during Zachary Taylor’s administration. In addition, she received a $30 per month pension as Richard’s widow.

She also continued to run the tavern that they owned. Eventually, she combined the post office and tavern in one building with the post office in front and the tavern in the back.

Ann worked hard and watched her spending. Upon her death, she left $20,000 for her children. Read more about Richard and Ann Gentry.

Henry Thomas

Henry arrived home and went back to his Missouri life, but with new stories to share with friends and family. Included was the story of carrying Col. Gentry out of the swamp when he was mortally wounded.

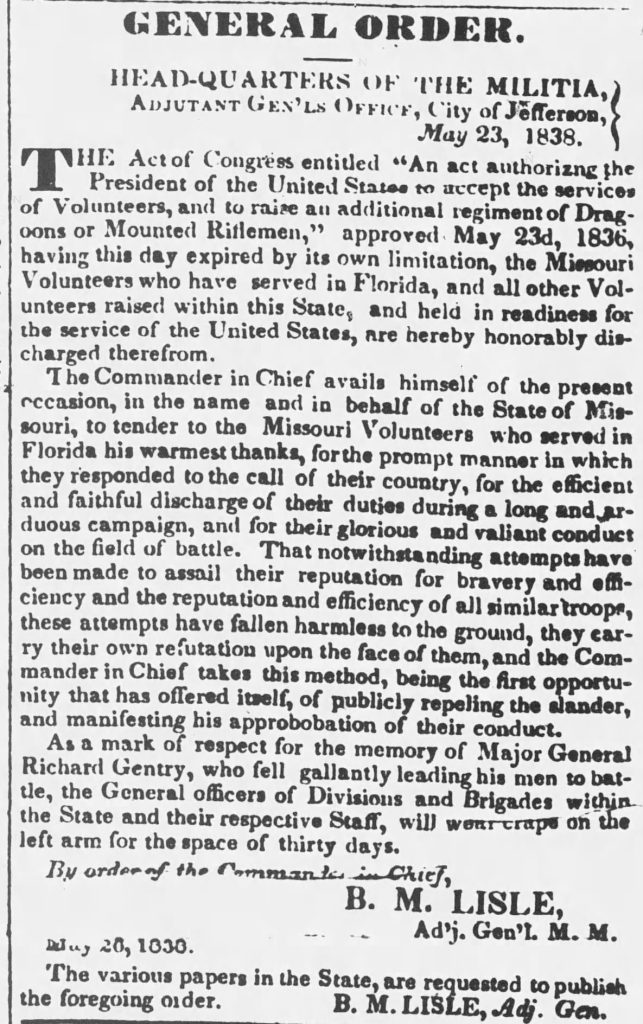

Toward the end of May 1838, he was formally discharged when the government discharged all the men who had served in the Seminole Indian War. Additionally, other men who had been on alert to serve if needed were also discharged. In the notice, they recognized the men for volunteering and for “bravery and efficiency.”

On July 15 of that year, Henry married Elizabeth Brown Donaldson in Monroe County. They went on to have 12 children, 11 who grew to adulthood.

Learn more about Henry’s life in Too Many Thomases or by reading Henry’s biography.

Afterward

Many accounts of this campaign exist and the details vary greatly. In this article, many details that were not particular to Henry Thomas and the Missouri Volunteers were generalized or omitted.

Despite efforts of the National Park Service, as of 2015, the exact location of the Battle of Okeechobee had not been determined.

Featured Image: AI generated using Google Gemini using a description and no input image.

Prompt: Big Decision

#52ancestors52weeks

Hunting

Hunting