When doing local research, genealogists and historians in the area can be very helpful. They can point you to resources that you don’t even know that you need. Word of caution, however, is to not take their word for it if they say they don’t have any information about the family you are researching. They are likely trying to keep you from wasting your time, but it is important to keep focus. It is likely that you know a lot more about your family than they do and it is unlikely that they have come in contact with information for every family that ever lived in the area. So, keep looking and keep asking questions.

Historic Fallsington

Quite a few years ago, we were doing research in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, just outside Philadelphia. One of our stops was at Historic Fallsington. It was close to the area where we believed the Stackhouse family lived during the William Penn era.

The history center in the tiny town had documents, offered tours, and even sold some items of local interest. So, we talked to the woman working there about the Stackhouse family in hopes that we could find some piece of information to help in our research.

Arrival

Arrival

We told her what we knew of the family’s arrival in Bucks County. We knew they had come about the time William Penn was bringing people to Pennsylvania. There were claims that he had been on the ship Welcome with William Penn, but that seems to be claimed by far more people that there was space on the ship. We would later learn that Thomas and his wife Margery had come to America on the boat “The Lamb,” a ship of 130 tons, in 1682 as a part of William Penn’s fleet. They had left Liverpool in the summer and arrived in Pennsylvania on October 22, 1682.

With Thomas and his wife Margery were Thomas’ nephews Thomas and John, Ellen Stackhouse Cowgill, and Ellen’s children. Ellen was thought to be Thomas Sr.’s sister as a sister Ellen is mentioned in his will. I have read that her husband had been put to death over his religious beliefs. However, I have not verified information about Ellen. It is known, though, that this family and the others on the ship were Quakers from Yorkshire, England.

Seeking Information

The woman very kindly told us that she did not believe the center had any information on anyone with the name of Stackhouse. She said that the name was completely unfamiliar to her and that she didn’t know of anyone with that name living within the township at any time.

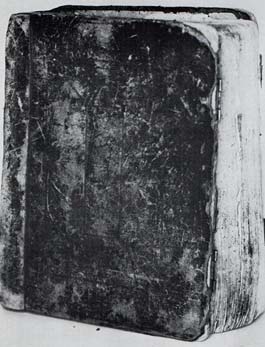

We asked if the history book of the township might have anything about the family. It was 300 pages and had been compiled in 1992 to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the township. Again, she emphasized, apologetically, that she had never seen the name Stackhouse anywhere. And, we couldn’t easily check the book as it did not have an index.

We decided to buy the book anyway hoping to at least learn about the area. And, we found that to be a wise decision.

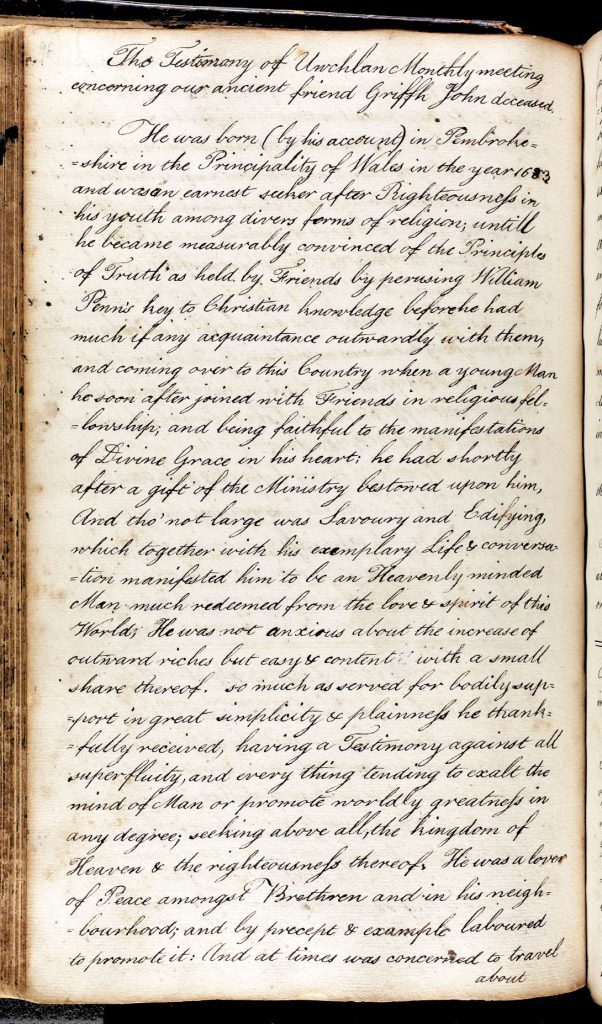

Branding (Photo the brand of Thomas Stackhouse)

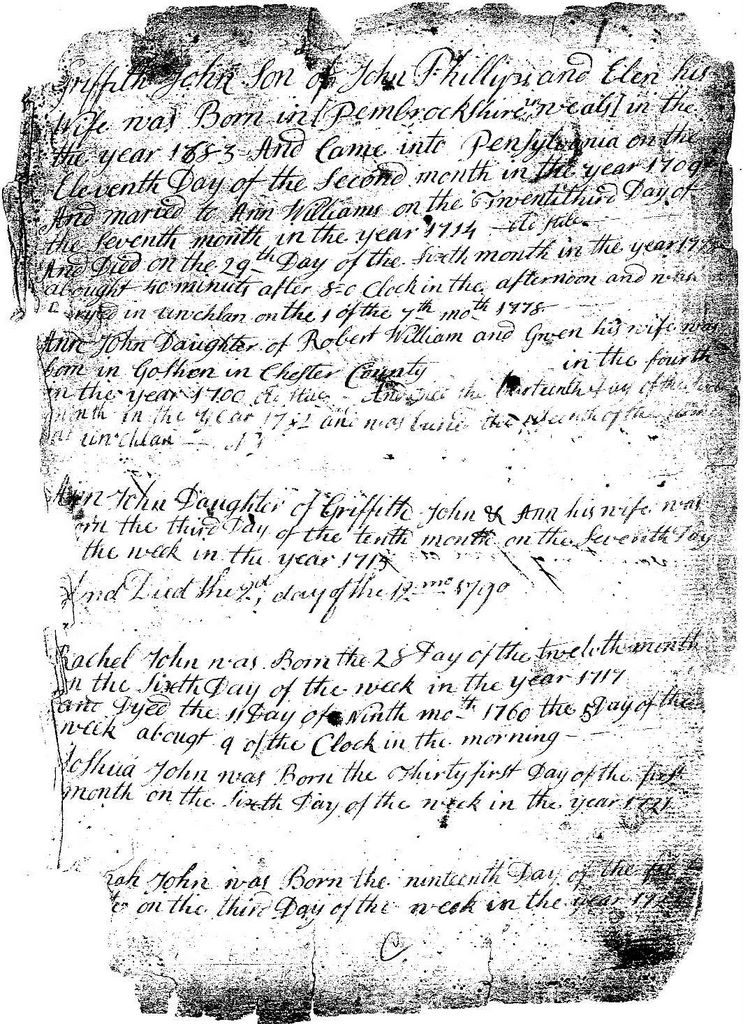

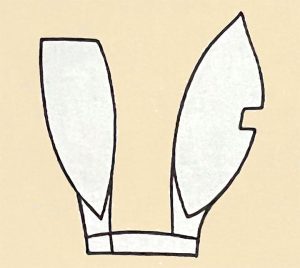

The first mention of the Stackhouse family I found in the book was on page 8 where it showed Thomas Stackhouse’s brand for his cattle. In those days, cattle were often branded by cropping the ears of cattle with a particular pattern. Even in the very early days of Pennsylvania, the brands had to be registered with the first being registered in 1684. Thomas Stackhouse’s brand consisted of cutting the top quarter (or less) off one ear (assumed to be the left ear) and notching the other ear on the outside half way down.

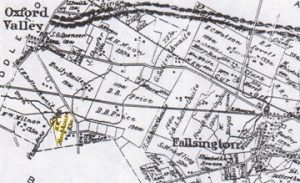

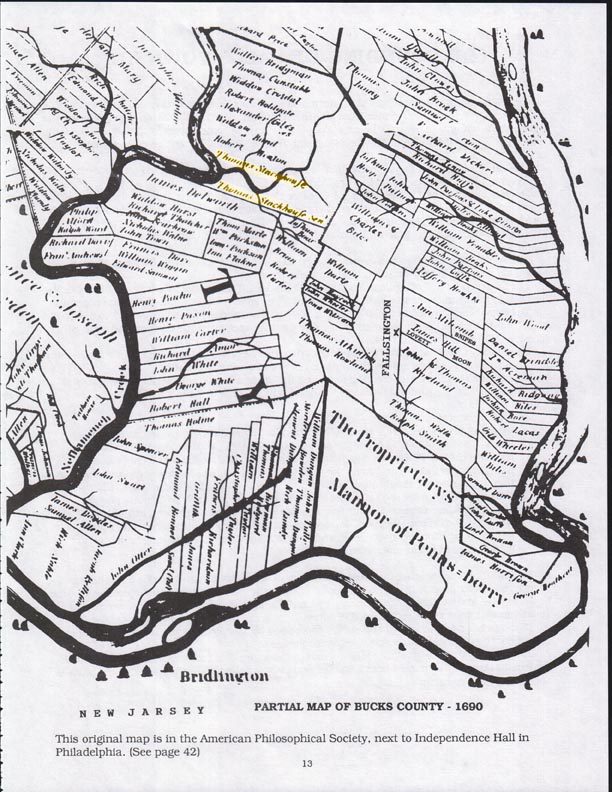

The Maps (1690 map)

The book included numerous maps, including land ownership, dating back as far as 1690. Three of those maps showed land owned by the Stackhouse family. The 1690 map showed that Thomas Stackhouse Sr. and Thomas Stackhouse Jr. owned land along Neshaminy Creek south of Newton and about 7 miles from Fallsington. The exact size of their properties seem to change over time with Thomas (not sure which one) purchasing an additional 50 acres over their original lands in 1686. John Stackhouse purchased 200 acres of land about 1695. Later information shows land owned by him to be over 300 acres.

A later map from the 1800s shows the location of Stephen Stackhouse’s property. It is under the name of his grandson who later lived on the property. It was known by descendants as The Old Homestead.

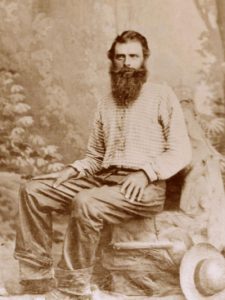

Pennsbury Manor

The book contained a lengthy story about Pennsbury Manor. Russell Stackhouse was a caretaker of Pennsbury Manor in the 1900s. He was mentioned in the book as he had told his successor the story of how the Pennsbury Manor historical site came into existence. As it is told, Charles Henry Moon, a local surveyor, repeatedly pressured the then president of Warner Company, who owned the property where William Penn had once lived to turn 10 acres of the property over to the state for a site honoring Penn. Finally, they gave in and the current site was created. Apparently, Mr. Moon was aware that there was a provision in the deed to the land that the specific piece of the property was to go to the state for this purpose. However, it took a good deal of time and insistence to make it happen.

Other Mentions In The Book

The Supporter of England

The book also mentions a John Stackhouse, who along with numerous others was charged with treason as he supported England. I have been able to verify that this occurred, but I do not know which John Stackhouse this was as they were numerous after a few generations. It is also a bit surprising as the Stackhouse family had apparently come to American because the Quakers were persecuted by the English government. It begs many questions about why he supported England and if he was of the same family.

1914

Stackhouses apparently remained in the area throughout the years. The farm and business directory for Bucks County that was included listed a Stackhouse.

There were other photos and mentions for other families of interest as well. All in all it was a good purchase and we were so glad that we had went ahead and bought the book even though the staff did not know of the Stackhouse family. It gave us new insights and added to the research that we were doing.

The Connection

Rod’s Klinefelter family line connects to Elizabeth Mason Stackhouse, who married Joshua Brooks. Their daughter Ann married into the Klinefelter family. Elizabeth, who lived to be 99, and Joshua left Bucks County behind and moved across the state to Pittsburgh. There Joshua was in business with her brother Mark.

Elizabeth is the daughter of Stephen Stackhouse and Amy Vandike, who married in 1787 at the Presbyterian Church in Newtown, only a short distance from the original Stackhouse property. From there the belief is that Stephen is the son of John, who is the son of Thomas, who is the son of John who immigrated to America from England in 1682. However, despite years passing, I am still in the process of proving this relationship to my satisfaction. The process has been complicated by inconsistent “facts” and interpretations of records. Got to keep on digging!

Arrival

Arrival

Neighbors

Neighbors