Palmyra In Its Infancy

In the early 1870s, Palmyra, Nebraska, 34 miles west of Nebraska City was in its infancy. Only being platted and surveyed recently, Palmyra was ready to grow and to have business boom. Being situated along the railroad, Palmyra was perfect as a point of import and export.

In the fall of 1870, William Ronald purchased his first property in Palmyra. He bought a hardware business from Sylvanus Brown. William’s brother Robert would soon be a Palmyra businessman, too.

A Growing Village

Mid-1870s

By the mid-1870s, the town was estimated to be between 200 and 300 people. Two hotels existed in town – the Centennial House and the Keystone House. Robert Ronald was the proprietor of the latter. The Masons and other groups had been organized, along with Methodist, Presbyterian, and Catholic Churches.

The village had a flour mill, dealers in agriculture implements, lumber, dry goods & groceries, and general merchandise. William (W. B.) Ronald owned the hardware and furniture store in town. In the back of the store were additional rooms that the family lived in. Additionally, you could buy hats, sell grain, engage a blacksmith, or see Dr. White, who was the town’s physician and druggist.

In 1876, the rail station, which included a telegraph office, was kept busy. 244 rail cars of goods were exported with largest exports being corn, wheat, and hogs. Meanwhile, the biggest imports were lumber and coal.

Late-1870s

In 1878, Mr. Frost of Iowa moved to Palmyra to take charge of the Keystone House, which Robert owned. By the next spring, Robert had built a new 30 ft. x 50 ft. livery on Fourth Street just east of the Keystone House.

The livery was one of two in Palmyra. People of the village had choices. By 1879, Palmyra had two hotels, two grain elevators, two hardware stores, two general merchandising stores, and two physicians. But, the town had only one saloon. Palmyra had also added a fourth church, an additional physician, and a business that made cheese.

Business, Business, Business

By the fall of 1880, William was expanding his business. He built a new store that was the largest store in town. Besides the main floor, the store had a 66 ft. x 32 ft. hall upstairs that could be used for lectures and other events. The hall was the largest in the county outside Nebraska City.

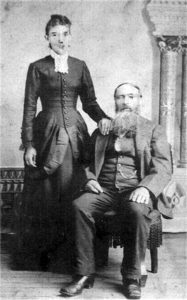

William, however, did not stay around long to enjoy the new larger store. In January 1881, William sold his hardware business to his brother Robert.

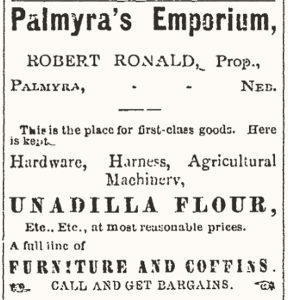

After Robert took over ownership of the hardware store, he called it “Palmyra’s Emporium.” It was said to have “first-class goods,” hardware, harnesses, agricultural machinery, furniture, and wall paper. In addition, the business included coffins and undertaking. Unrelated to hardware or home wares, the store also had Unadilla flour, which seemed to be popular in town despite the town having their own flour mill.

At the end of June, 1881, W. D. Page, who had been dealing in groceries and dry goods, expanded his business. He bought out Robert’s hardware store. And, he purchased the Keystone House and livery, too.

Life After Palmyra

William and Robert left Palmyra within less than a year. Both continued to own and work in businesses after they left Palmyra. However, they never had a business together or lived in the same area as each other again.

William B. Ronald

Two months later his wife Margaret Ann, whom he had married in 1870, filed for divorce on the grounds of abandonment. According to family, he went to Indian Springs, Missouri when he left his wife. However, I have not uncovered any evidence of his travel.

Cherokee, Kansas

On April 23, 1881, the Nebraska City News printed that William and Margaret had been granted a divorce. That same day William married Ellen Raymond in Cherokee, Crawford County, Kansas. Raymond may have been a married name as it is said that she was a young widow. However, information on Ellen is quite elusive.

According to the newspaper, about the time William married, he opened a stock of boots and shoes in Cherokee. The village had been founded 10 years earlier and was now thriving with over 500 inhabitants. It was to grow over 95% during the next decade.

The family also believed William owned a small grocery store during his time in Cherokee. I am not sure if this is the case or if there was confusion about a store he later owned. In any case, William’s business in Cherokee didn’t last long.

Indian Springs, Missouri

By the end of 1881, William sold his property in Cherokee. William and his wife moved to the new resort town of Indian Springs, Missouri by the beginning of February. Six weeks later, William claimed the healing water of the mineral springs had resulted in hair growing where he had once been bald and that it had cured his wife’s indigestion.

Soon, William and James Robinson of Neosho, Missouri began building a new two story hotel. The hotel was 55 ft. by 68 ft. and contained 29 rooms. It was named Planter’s House and was completed around July 4, 1882. It was close to the healing mineral springs that had drawn people to the area. The hotel was advertised as “A favorite resort for invalids.” It also had sample rooms for business men to use.

York, Nebraska

William’s wife became sick with tuberculosis and they moved back to Nebraska. After his wife died in December, 1883, William bought a small store on the east side of the square in York, Nebraska. He advertised that oysters, fruit, candies, and cheese were available in his store. The next year he advertised that birch beer, ginger ale, dried beef were available at his establishment.

In the 1885 census, he listed his occupation as confectioner.

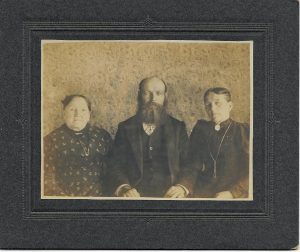

Sherman Center

In October 1886, only a few months after marrying Angeline Cutshall, who was 35 years his junior, William dissolved two business partnerships in York, Nebraska. According to family, he then went to Sherman Center (originally called Shermanville and now a ghost town) in Kansas. There, he purchases a livery barn. His wife stayed in Nebraska with family until the following October. At that time, his wife and their 5 month old son joined him.

The town had just been started a few months earlier and officially established in September. However, Goodland was founded a few miles to the south. Goodland won the election for county seat, something several towns including Sherman Center were vying to get. Additionally, the future railroad planned to go through Goodland. Sherman Center quickly lost business. Thus, William and his family returned to Nebraska where he died in July, 1888.

Robert Ronald

Robert’s sale preceded his exit from Palmyra and the state of Nebraska. Robert, his wife Clara whom he had married in 1872, and their children headed to the west coast. Their reasons for moving are unclear. Perhaps they just got the urge for adventure or as the newspaper indicated maybe they wanted to try a new climate.

Of course, it could also have been that Palmyra just didn’t have enough traffic to support his businesses. One writer of an article about the time William left Palmyra indicated that the town just wasn’t drawing enough business visitors and that it was falling behind other towns in terms of growth. The author suggested that the businessmen of the village needed to step up and help the town grow.

San Francisco

Although Robert left the hardware business, he wasn’t done selling goods, but like William the goods he sold and the location of his business changed.

Robert purchased a 40 acre farm in Santa Rosa, California. By November, he was selling fruits and vegetables in San Francisco.

Then in 1882, he sold the farm and purchased a meat market. After that he worked in various jobs until 1898 when he moved to Oregon. It was at that time that Clara was granted a divorce for desertion.

Robert died in Oregon City, Oregon of pneumonia in 1903. Based on Robert’s possessions at the time of his death, he appeared to have returned to farming during his time in Oregon.

To add a bit of confusion, his obituary mentions Clara as his beloved wife. Meanwhile, his death certificate lists him as a widower. Clara was definitely still living and as far as I have found they were divorced. She is not listed as an heir in his probate records.

There is more to each of their stories: their trips to America, life in New York and Wisconsin, and details of their family lives. Far too much for one article. But, great stories for another day.

Indiana Bound

Indiana Bound

The Interviews

The Interviews

Arrival

Arrival

Neighbors

Neighbors