Churches provide a space where anyone is free to wander in and join the congregation. They also often provide space for activities – some church actives, some for the community, and some for specific families. In addition, the church records often contain a wealth of genealogical information.

History With Churches

Both my husband’s family and my family have extensive relationships with churches of various denominations. A few years ago, we had the opportunity to attend the 250th Anniversary of Old Pine Church in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is rich in both American history and the history of my husband’s family.

Rod’s ancestors signed the call for Reverend Duffield in the early days of the Old Pine and his 7th great grandfather was the first sexton of the church. However, as family members died and moved west, the association with the church ended. Read more about Old Pine.

Chartering A Church

The association with the Palmyra Presbyterian Church in Palmyra, Nebraska, however, has lasted the entire time the church has been in existence. And, next year, the church will celebrate its 150th Anniversary. The main celebration planned for May 4, 2025 with other events throughout the year.

The association with the church began when my husband’s 3rd great grandmother Mary (Gourley) Ronald, his great-great grandparents Arthur Reid and Margaret (Ronald) Thomson, and Margaret’s brother William B. Ronald became charter members. They made up one third of the charter members of the small church.

Roles in the Church

Members of the family are still active in the church today. Over the many decades, members of the family have served as church officials, teachers, participated in women’s groups, participated in Bible School, been elders, etc. For instance, George Thomson served as an elder and in 1941 Arthur Klinefelter “Art” Thomson was a member of the church board.

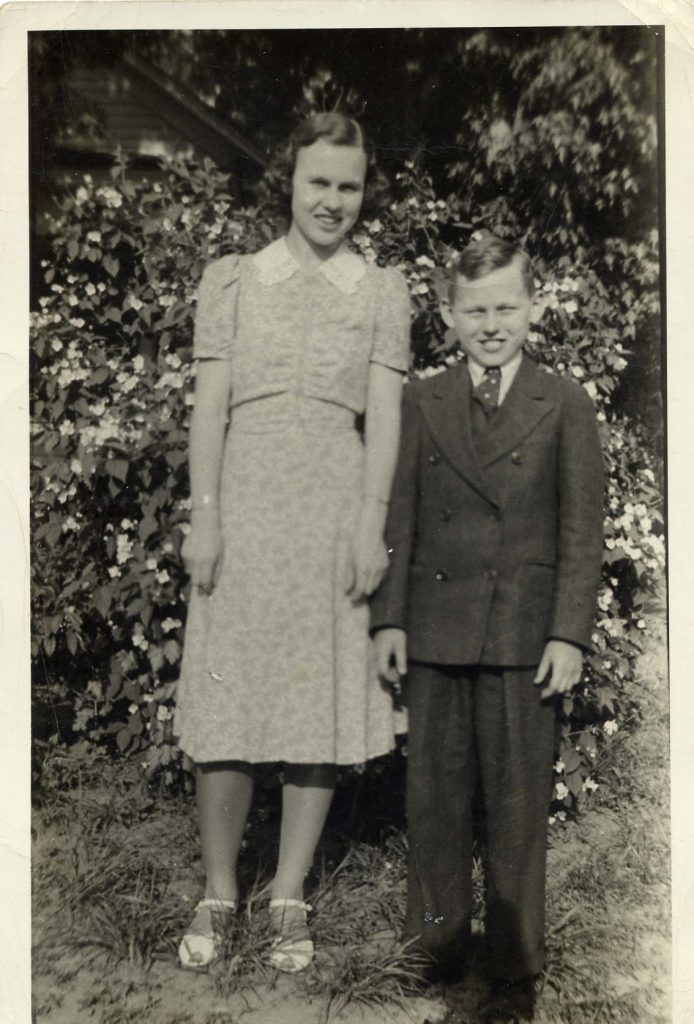

Music is also an important aspect of a Presbyterian Church. Local music teachers provided recitals at times in the church. In 1937, Alma Thomson was one of the students who performed in the recital. Arthur K. Thomson’s wife Verna (Wall) Thomson was also known to sing at church events. In more recent years, Emma (Bremer) Faulkner sang in the church choir. However, I am sure many others in the family were involved in providing music for the church throughout the years.

Life Events

Funerals

Funerals

When asking a family member recently about who in the family that had passed had their funeral held at the Palmyra Presbyterian Church, the answer was, “Everyone!” Well, that was an exaggeration, but was on the right track.

Of the charter members, funerals were held in the Palmyra Presbyterian Church for Arthur Reid Thomson and his wife Margaret. It likely that Mary Ronald’s funeral was also held there as she died at their home. However, given that she died before 1900, it is also possible that the funeral was held in the home. William B. Ronald died at York, Nebraska and was buried there.

Over the years, various family members funerals were held at the Palmyra Presbyterian Church. Just a few in the following generation include Arthur Reid and Margaret (Ronald) Thomson’s children: Mary A (Thomson) Orrison, and Herbert James Thomson. Additionally, Flora Marion Bunten, granddaughter of Mary Ronald through Mary’s daughter Jane Ronald and her husband William Bunten had her funeral at the church.

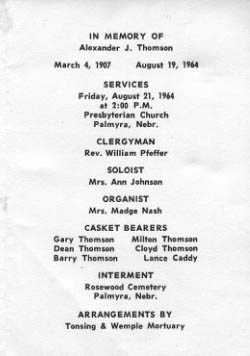

In the next generation, a few whose funerals were held at the church include: George Thomson, Alexander Thomson, and Arthur K Thomson. Funerals of family members continue to occur in later generations. For instance, Sandra (Thomson) Stickney, and Sandra’s grandson Alexander Thomson.

Judge Sharpless Klinefelter’s funeral was held at the church only days after his 100th birthday party was held there. In addition, there were funerals for those who married into the family. A few of the spouses are: Blanche (Klinefelter) Thomson, Donna (Van Allen) Thomson, Verna (Wall) Thomson, and Kenneth Leith (husband of Virginia Thomson).

Members of the family also served as pall bearers and in other capacities for many other funerals for family, friends, and neighbors.

Marriages & Baptisms

Palmyra Presbyterian Church was also the scene of many happier occasions, such as, marriages and baptisms.

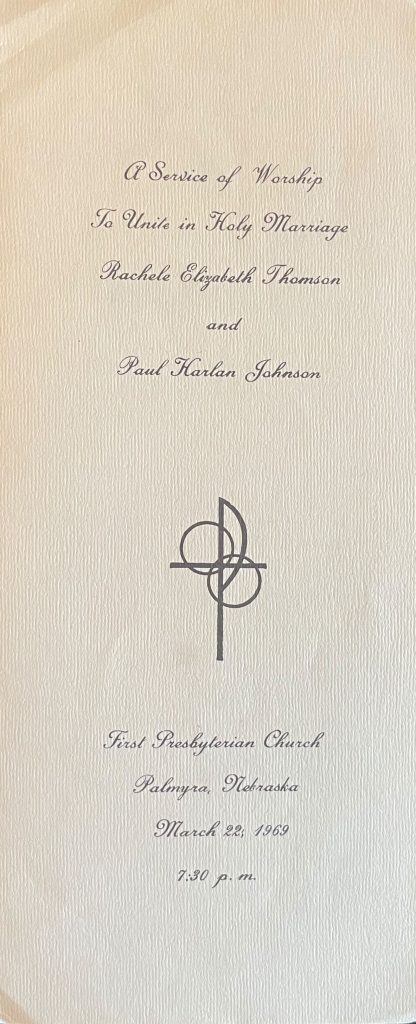

In the early days, many of the marriages were held in the bride’s home. However, over time marriages in the church have become more common. Some of the weddings at Palmyra Presbyterian Church include my husband’s parents: James Thomson and Janice Helm; his sister: Jackie Thomson & Duane Bremer, and his niece: Emma Bremer and Zachary Faulkner. His aunt Rachele also married in the church as did Georgia Faye Thomson, daughter of George and Viola (Lanning) Thomson.

Rachele (Thomson) Newbury’s children Clayton Johnson and Paul Johnson were just two of the many family members baptized in the church.

My husband’s mother’s family, although not living in Palmyra, even had a marriage at the church when Arlin Reuter, a cousin, married Lucy Ann Ikenberry, a local woman, at the church in 1963.

Other Events & Celebrations

The church was a gathering spot. As such, it was used not only for church events, but also for family and community events. One of most unusual events was a lard making demonstration. That wasn’t something I would expect at a church.

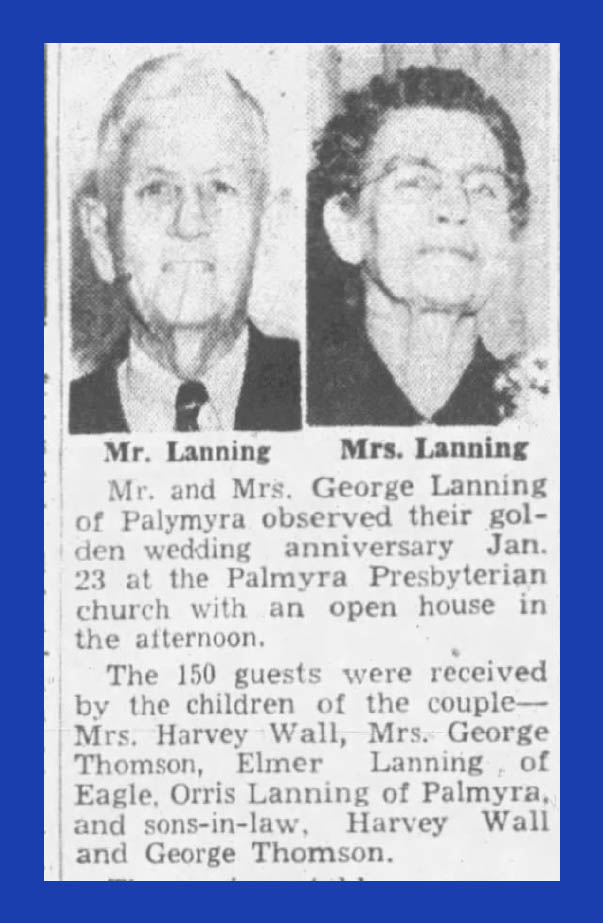

More traditional events that have been held at the church are the 50th wedding anniversary celebration for George and Jessie (Bunten) Lanning, which was celebrated with 150 people. Their marriage was likely a much smaller event being held at the Bunten homestead in 1901. A reception for my husband and me was even held at the church after we married in my home state.

Birthdays or other family celebrations were also held at the church. Besides Judge Klinefelter’s birthday party, a 65th birthday and retirement party was held for Janice Thomson in the basement of the church for both family and community members.

Likewise, church functions sometimes took place at one of the Thomson residences. For instance, in 1898, the Sunday School Picnic was held in Arthur Reid Thomson’s grove.

Have info about the Palmyra Presbyterian Church?

If you have information about the history of the Palmyra Presbyterian Church or know of descendants of any of the charter members (especially those not related to this particular family), please share with the 150th Anniversary celebration planning committee. Do so by contacting Jackie Thomson-Bremer. If you don’t have her contact info, contact me.

Charter Members

Mary DeCou

W J Dougall

Emma Dougall

William Dunlap

Jane Dunlap

Robert Dunlap

Moriah McGonigal

Elsie Smith

Mary (Gourley) Ronald

William B. Ronald

Margaret (Ronald) Thomson

Arthur Reid Thomson

Funerals

Funerals

To me Uncle Pat, great-uncle actually but we never made that distinction, was always an old man. Everything about him was old. He looked old, smelled old, and had old things. I remember visiting his home and feeling very uncomfortable, not because Uncle Pat and his wife Aunt Verda weren’t nice to us, but because everything was old. Not a lot seemed to have had a lot of care given to it.

To me Uncle Pat, great-uncle actually but we never made that distinction, was always an old man. Everything about him was old. He looked old, smelled old, and had old things. I remember visiting his home and feeling very uncomfortable, not because Uncle Pat and his wife Aunt Verda weren’t nice to us, but because everything was old. Not a lot seemed to have had a lot of care given to it.

It is said that Uncle Pat lost his interest in life and drive to achieve after he lost his only biological child and the only one who could carry on the family name. At the time of Paul’s death, Uncle Pat was working as a pressman for Inland Printing, a position which he had held for at least 15 years. He seems to have left that job later in 1941 or in 1942.

It is said that Uncle Pat lost his interest in life and drive to achieve after he lost his only biological child and the only one who could carry on the family name. At the time of Paul’s death, Uncle Pat was working as a pressman for Inland Printing, a position which he had held for at least 15 years. He seems to have left that job later in 1941 or in 1942.

Summer of 1849

Summer of 1849

Purchase The Property

Purchase The Property