Rod’s 4th-great-grandfather Jesse Klinefelter and multiple of his brothers were steamboat pilots and captains. Initially, they piloted boats on the Ohio River primarily between Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Cincinnati, Ohio.

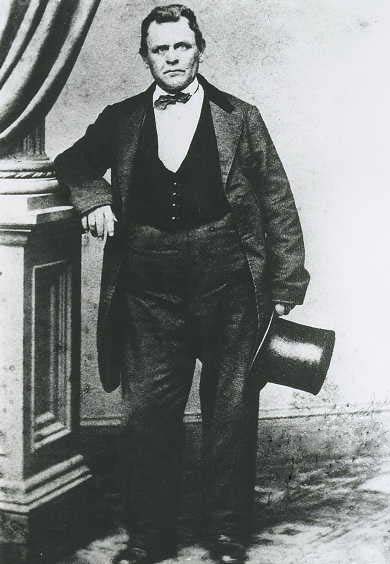

Jesse’s brother John became well-known as the captain and owner/co-owner of several different boats over the years. One passenger described Captain John Klinefelter as a stout Pennsylvanian of German descent with a face that indicates it would be difficult to keep him from moving his boat forward. He had the reputation as one of the most efficient and careful men on the river.

After many years on the Ohio, John began running boats on the Mississippi River.

The Pennsylvania

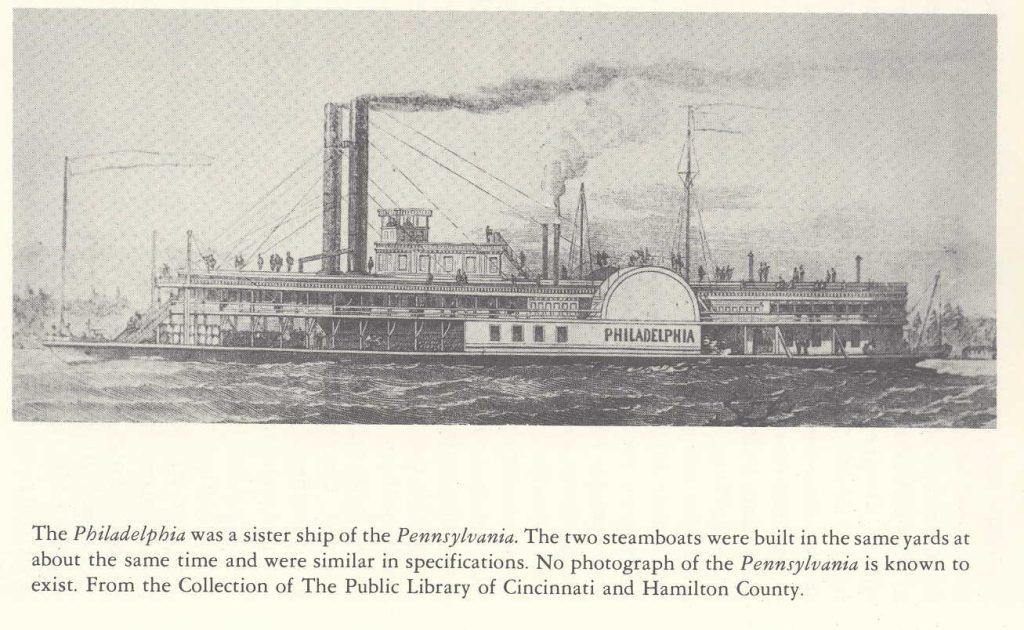

The 486-ton Pennsylvania started operations in 1854. A boat with the name Pennsylvania existed by at least 1848, but that appears to have been a different boat. In any case, Captain Klinefelter became 50% owner in the Pennsylvania with the pilots and engineers owning most of the remaining 50%.

The Pennsylvania was 247 feet long and 32 feet wide. She had fine furniture and was a “magnificent specimen” being “one of the largest, handsomest, and best officered, and in every way most desirable boats to travel on.” She, with Captain John Klinefelter as master, was known “for speed, good living, [and] punctuality.”

Heading North

The Pennsylvania was loaded with cargo and passengers when it left New Orleans on June 9, 1858. She would pick up others at Baton Rouge, Vicksburg and other locations along the route. Including the passengers, officers, deck hands, and other crew, it was estimated that the Pennsylvania was carrying a full load of cargo, some $40,000 in its safe, and 380 to 450 people with some estimates as high as 500.

On the ship were members of an opera troupe, German immigrants, William R. Harris Supreme Court Justice of Tennessee, a plantation owner, at least two priests, a couple Sisters of Mercy, and various people well-known in their local social circles.

The Explosion

By 6:00 the morning of the following Sunday, June 13, the Pennsylvania had reached Harrison’s Wood Yard, a point about 70 miles downriver from Memphis. Most passengers were still sleeping or were just waking up for the day. Captain Klinefelter was already up, dressed, and had gone to the barber on board for a shave.

Additionally, the second engineer had taken over from the first engineer. The fire bed had been recently cleaned and the fire started. He made sure everything was working and had tested the water in the boilers after he came on duty. At that time the boat was only producing about 130-135 pounds of steam and the boat was moving very slowly up stream.

Suddenly, while Captain Klinefelter, having finished his shave, was speaking with Henry Spence in the saloon, they heard a horrific noise. The room immediately started filling with steam. They hurried through the water closet passage to the hurricane deck where they met up with the barber, who had also rushed outside.

The Situation

It was instantly clear that the boilers had exploded and that the damage was massive with the greatest impact forward of the wheelhouse. The smoke stacks were gone as was a portion of the deck. The explosion had blown people and much debris off the boat into the waters of the Mississippi River. Others had been blown to a location that provided no option for escape except to jump into the river. At that point, some swam back to the boat and attempted to climb back aboard, others swam for the shore, and others grabbed onto debris hoping to stay afloat until they could be rescued. Other people were instantly killed, were trapped, or were lucky and were flung out of harm’s way or were easily removed from the debris.

Jumping Into Action

The captain, barber, and a cabin boy launched a life boat. Meanwhile Henry Spence broke a skylight to let the steam out of the area below so that people would not suffocate.

The boat started moving downstream with the current. So, the men attempted to anchor it, but the current was swift and the water was deep. The Pennsylvania kept drifting. Captain Klinefelter and some men tried to take a line ashore with a yawl, but were unsuccessful.

At this point, the captain sent the yawl downstream to get an empty wood boat that was along the water at Harrision’s Wood Yard. About the same time, some men from the wood yard started moving the empty flat boat up stream. It was hard to maneuver as they had no oars and were using a few boards as oars. They met up with the yawl and they managed to get the flat boat along side the Pennsylvania. The idea was to get as many people off the boat as possible. Then come back for others or for possessions and goods.

The Fire

As the captain and any other crew members that were not severely injured attempted to get passengers to leave their worldly goods behind and get on the flat boat, a fire alarm rang out. Almost immediately flames, believed to be fueled by barrels of turpentine in the cargo hold, were engulfing the Pennsylvania.

They quickly rushed to fill the flat boat with all the people they could before the fire reached them. Meanwhile, one man claiming to have money, own a plantation, and have slaves offered to give it all to anyone who would rescue him from a mass of debris. However, with the flames advancing, the crew had to make the hard choice to save as many passengers as they could. They had to leave the man behind.

The Escape

Captain Klinefelter was the last to jump onto the boat. They had a difficult time shoving away from the Pennsylvania. The heavy load of people, limited trained crew members, and boards for oars made it challenging. Finally, they turned the flat enough that the river current caught it and pulled them away from the Pennsylvania. However, some of the passengers were badly burned as they made their escape. It was believed that if they had been even a few moments later, the casualties would have been much greater.

After they pushed away, they saw people who had apparently been in their quarters rushing toward the boats edge with their trunks and boxes. With the fire and limited control over their movement, Captain Klinefelter did not have the option to go back for them. Sadly, the people who had tried to save their belongings likely ended up losing their lives.

About a mile or so downstream the flat came upon Ship Island and they tied up to some trees and waited for help.

The Rescue

Immediately following the explosion, people living along the river got into their boats and went to rescue those who were in the water. Meanwhile, those on the flat waited for a boat to come by. They had no food, water, or significant shade. They had no medical supplies to tend to the wounded.

The Imperial was the first big boat on the scene. The captain and crew jumped into action tending to the injured and feeding and hydrating the passengers of the Pennsylvania. Next on the scene was the Kate Frisbee that took many of the injured on board. The injured had cuts, bruises, internal injuries, and burns.

The Diana arrived about 6 hours after the explosion. She did not take as many passengers as she was already overflowing. However, passengers on the Diana, and likely the other boats, started taking up money to help pay for medical costs and to help those that had no money and nowhere to turn.

As the boats left carrying away the survivors, Captain Klinefelter headed to the Pennsylvania, which had lodged and sunk near the shore some two and a half miles downstream in hopes that some passengers had survived or some property could be salvaged.

Henry Clemens

Many of the injured were taken to Memphis for medical treatment. Among them was Henry Clemens, an assistant clerk. Henry was only 19 years old and was the younger brother of Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain. Although initially not thought to be badly injured, Henry had internal injuries dying a few days later. Samuel wrote about Henry’s condition in a letter to their sister on June 18. Later he wrote of the Pennsylvania’s demise in his book “Life on the Mississippi.” That work includes his version of the story surrounding the explosions of the Pennsylvania and his brother’s death. It also includes a sketch depicting him at the side of his brother as he lay dying in a hospital in Memphis, Tennessee.

It was said that he never got over losing his brother. That may have been a bit of survivor’s guilt. Samuel had worked on the Pennsylvania as a pilot in training and was suppose to be on the boat that day. However, he had gotten into an argument with the pilot Mr. Brown on the trip down from St. Louis to New Orleans and he said that he could not make the return trip on the same boat with the man. Thus, five minutes before sailing, Samuel left the Pennsylvania.

Confusion

As the news of the explosion spread, much confusion spread, including whether Henry Clemens was uninjured, injured, or had died. Confusion occurred over other specific passengers, the number of passengers, the number that had perished, and exactly what had happened.

Confusion wasn’t unexpected given that the injured and surviving passengers and crews were spread across multiple boats. A notable, who had confusing reports regarding his survival, was William Woolford, the son of the city clerk of Louisville, Kentucky. The reports being mixed as to his status, the family had hoped for survival. But, it was not to be. One of the most notable to die was William R. Harris, Supreme Court Justice of Tennessee. He was returning from a trip to New Orleans. He succumbed to his injuries in Memphis. His brother was governor at the time and was tasked with finding his replacement. Additionally, the ship’s register had burnt in the fire rendering the captain unable to determine how many people were missing or dead.

As is common in the case of a disaster, everyone’s story varied. Similarly, those who weren’t even present speculated just a bit too much. As such, I have tried to use as many first-hand details as possible. For instance, many stories report that Captain Klinefelter was getting a shave. However, Henry Spence detailed how he was with the captain at the time of the explosion; thus, his version is used for aspects related to himself and the captain while they were together.

The one thing that was for certain was that it had been lucky that the explosion occurred so early in the morning. Otherwise, more people would have been in the forward sections of the boat where they congregated during the day. Thus, more people would have been injured and died.

The Cause

So what caused the explosion? John Campbell of J. H. Campbell & Co. of New Orleans, who had been a steamboat engineer in his younger years, was attributed with telling a story that he had been up by the boilers and that the engineer was not at his post until just prior to the explosion. He supposedly learned that the engineer had been in the company of women. Mr. Campbell died in Memphis; thus, all reports of his story were not first hand.

During the investigation into the cause of the explosion, statements were taken in an attempt to prove the validity of Mr. Campbell’s statements. The engineer’s associate stated that he was on duty as did the second mate. The investigators did not find the statement attributed to Mr. Campbell to be strongly corroborated. However, they decided that the engineer must have been neglecting his duties because they didn’t think such a disaster could possibly occur if an engineer was on duty. As a result, the engineer lost his ability to be an engineer on any steamboat.

Accusations Against the Captain

Survivors reported that Captain Klinefelter had acted in exemplary fashion. They said that he had done everything he could to save the passengers and contents of the Pennsylvania. He had managed the disaster without many of his trusted crew, as many of the engineers, clerks, and deck hands were injured, missing, or killed.

A Thief

All of that did not stop the Memphis Avalanche from printing accusations against the captain. They called into question his character with many “stories,” focusing primarily on him being a thief and stealing the money of passengers. It seemed to stem from a man named Vasser that was killed. His wife claimed that he had given the clerk $10,000 to put in the safe.

The paper claimed that the safe was likely thrown to a place that it was barely touched by fire. And, that it would have withstood the amount of fire it had received. They went on to claim that he took it north with him and that he tried to get away as quickly as possible. When the safe was recovered, the paper argued that the safe purported to be that of the Pennsylvania could not possibly have been it. They felt the safe was in such poor shape that no one would have put valuables in it. They speculated that there had been a different “real” safe and that people had been deceived.

Heartless

Additionally, the Avalache claimed that he had been near Memphis on numerous occasions and never stopped to see the suffers. So basically, they accused Captain John Klinefelter of being a “heartless thief.”

Racing

The Avalanche also accused the officers of the Pennsylvania of wanting to stay ahead of the Diana. They indicated that pressing the boat to move so quickly upstream had led to the explosion. They went on to claim that necessary repairs that the chief engineer recommended to fix a fault with the pipe that carried steam from the boilers to the cylinders had not been done. And, the ship had continued to make trips on the river.

The Motive

The motive of the newspaper is unclear. They were new (or at least a new version of the newspaper) and perhaps they intended to make a name for themselves or simply liked sensational headlines. Additionally, no one named Vassar is listed among those lost in the disaster, but that is not meaningful as the passenger list burnt and not every life lost was mentioned. The lady with him was said to be at Aberdeen, Mississippi and destitute. Families with the name Vasser did live in that area at that time and appear to have been wealthy. Thus, having $10,000 with them as they traveled is not unreasonable. However, I have not yet found any records supporting the death of one of them in the disaster.

The Response

With his good name and reputation at stake, Captain Klinefelter felt a need to respond. Thus, he obtained sworn statements from people involved with raising the safe. He published a detailed article that included the statement and outlined the agreement with the wrecking company. There was also a statement on the amount of money taken from the safe. The article specified that the money was in the possession of a separate company. The money found was listed piece by piece (e.g. how many gold eagles, silver halves, Mexican dollars, etc.). It even listed “imperfect coins found and melted silver.

Captain Lemuel C Nims

One important statement was from Lemuel C Nims, captain of the submarine working the wreckage for the wrecking company. He detailed the instructions he had been given by the company, including to chain or band the safe closed if it was closed and such a step was feasible. He stated that at the time the safe was found that it was so badly damage that there was no way to secure the contents. Thus, the contents were removed.

Captain Nims stated that at the time the contents were removed from the safe 14-15 people associated with the recovery were present. Plus, there were other onlookers. All the paper money and boat’s documents were destroyed. The coins and some silver coins that had melted remained. Capt. Nims and the engineer cleaned the money and melted silver. They gave $60 to Captain Klinefelter for the expenses associated with watching the wreckage. They placed the remaining silver coins and melted silver in a box and the gold in a bag. The box and bag were then secured. He also indicated that based on the location of the safe before the explosion and the location it was found afterward that it likely took the wrath of the fire.

The Pilot

Sworn statement from the pilot of the wrecking sub supported Captain Nims statement. He added that when they first started raising the safe that some coins had fallen out. They had taken steps to prevent losing any additional coins. In addition, he stated that he was responsible for taking the money to St. Louis and he detailed his journey there on two different boats and the railroad including never letting the money out of his possession.

These sworn statements along with accounts of passengers that praised his efforts and attested to the fact that the boat was moving slowly discredited most of the allegations against the captain.

The Retraction

Many newspapers that had picked up the story printed Captain Klinefelter’s article and/or a statement basically exonerating Captain John Klinefelter. However, to date I have not found that the Advance, which appeared to have started and perpetuated the accusations ever retracted them.

By early September, Captain Klinefelter was again running a boat from St. Louis to New Orleans. This time it was the Gladiator.