by L. L. Thomson

Many people over the years have spent their later days in a retirement home. However, few have lived in a retirement home as many years as Elizabeth Mason (Stackhouse) Brooks lived at the Home for Aged Protestant Women.

Elizabeth’s History

Elizabeth Mason Stackhouse, Rod’s 5th great-grandmother, was born March 19, 1802 to Stephen and Amy (Vandyke) Stackhouse. Note: Vandyke has many different spellings in records with Van Dyke and Vandike being common. Her birth likely took place in Falls Township, Bucks County, Pennsylvania where the Stackhouse family had lived since they arrived in America in 1682.

In February 1822, Elizabeth married Joshua Brooks in Tulleytown, Bucks, Pennsylvania. In that year, he is listed in Falls Township. However, previously, he was listed in Newtown, Bucks, Pennsylvania. He is listed in tax records with William Brooks and John Brooks. William is believed to have been his father and the likely owner of the Brooks House in Newtown, which we visited.

Elizabeth and Joshua became the parents of Ann Rue, Emma Vandyke, Stephen S., Henry G., Sarah C. and Samuel S. Ann Rue married Jesse Klinefelter. They are Rod’s 4th great-grandparents. Ann married James Hendrickson after Jesse died.

In 1828, Joshua, Elizabeth, and their oldest four children moved west to the bustling city of Pittsburgh, where Joshua was in business with a member of Elizabeth’s family. They built stationary engines. Joshua was a skilled blacksmith.

Joshua died unexpectedly in 1869 while visiting his daughter Ann R. (Brooks) Klinefelter Hendrickson.

Home for Aged Protestant Women

In 1870, Elizabeth can be found in her daughter Sarah’s household. It is unclear if Elizabeth lived there the entire time between when Joshua died in July 1869 and March 3, 1874 when she moved to the Home for Aged Protestant Women (HAPW).

Why?

The obvious question is why did Elizabeth go to live at the facility? Even if she didn’t want to remarry or had no prospects for marriage, why didn’t she continue to live with Sarah or go live with one of her other children?

Sarah had a husband and two growing children at the time Elizabeth moved into the HAPW. Perhaps, the family needed the space Elizabeth had been occupying. There also could have been conflicts with three generations in the same space. It wouldn’t be the first time a family found multiple generations to be a challenge. So, for whatever reason, Elizabeth did not stay in Sarah’s home.

When considering Elizabeth’s other children, her oldest daughter, Rod’s 4th great grandmother, Ann Rue (Brooks) Klinefelter Hendricks, was a two-time widow. She had lost her second husband only a couple of months before her father died. By the time her mother entered the Home for Aged Protestant Woman, Ann was working as the Matron of the Poor House. So, she wouldn’t have had a place to house her mother.

Elizabeth and Joshua’s second daughter Emma Vandyke Brooks has been a bit difficult to trace. She was in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Muscogee County, Georgia with her brother Stephen; and later is in Missouri. Stephen, as mentioned, was in Georgia. Moving in with his family would have required traveling south, but it was post-Civil War so it was definitely doable. Yet, Elizabeth stayed in Pittsburgh.

Her son Samuel had drown while he was working as an steamboat engineer when he fell overboard on a run between Louisville, Kentucky and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. And, Elizabeth’s son Henry was also said to have died before 1870. The circumstances and exact date are unknown.

So, Elizabeth moved to the Home for Aged Protestant Women.

The Home

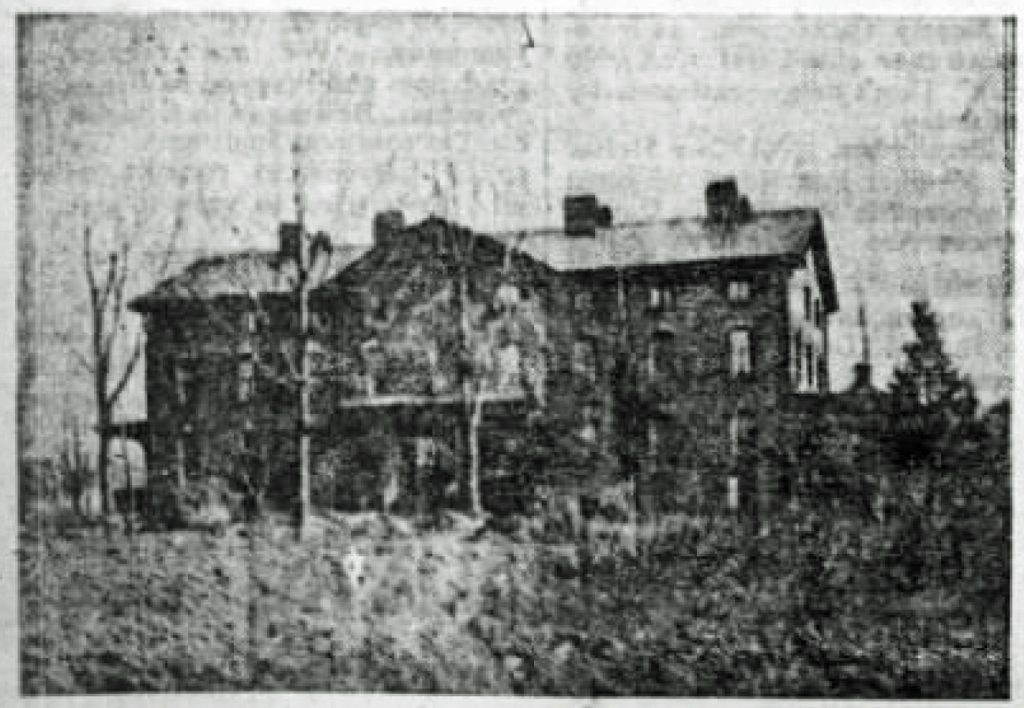

The Home for Aged Protestant Women, situated on five well-groomed acres near the Pennsylvania Line on Rebecca Avenue, had opened its doors only two and a half years before Elizabeth moved in. It had been founded by Jane Holmes on land donated by James Kelly. Oversight was performed by the Board of Managers and was an auxiliary of the Women’s Christian Organization.

The Application

Entry to the home required that the applicants lived in Pittsburgh/Allegheny for ten years, be over sixty years of age, and an application/acceptance fee. The women paid the $200 fee when they moved into the facility unless it was not practical or feasible for them to make the payment. Then an exception or alternative was arranged.

The payment wasn’t really for care as the cost over their stay far exceeded this amount. Instead, it was to “guarantee the respectability and good behavior of the inmates.” Additionally, they wanted the women to consider themselves paupers. Note: In this era, the word inmate simply referred to anyone in an institution of any type.

The Rules

In addition to being required to be respectable and have good behavior, the women were also prohibited from using tobacco or any stimulants. The facility was very strict about behavioral rules. The year after Elizabeth moved in, the managers evicted a woman for repeated violations.

To move in applicants had to sign the following:

In consideration of my admission into the Home for Aged Protestant Women, Wilkinsburg, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, as an inmate, subject to its rules and regulations. I, the undersigned, do hereby assign and transfer to the said Home for Aged Protestant Women, Wilkinsburg, Allegheny County, Pa., to and for its absolute use, all my property and effects, and with the same legal effect as if delivered into its actual possession; and I do further agree to and with the said corporation that if I shall hereafter receive or become entitled to any money or property of any kind, real or personal, I will at once give information thereof to the managers of said corporation, and will assign and transfer the same to the said corporation if I remain at the home. And I do also hereby engage and promise that I will comply with all the rules of the institution.

Witness my hand and seal this . . . day of . . . . A. D. 19…

(Seal)

Witness present.

Pledge from early 1900s

Source: Pittsburgh Press, August 11, 1901

After the women entered the HAPW, their room, board, care, and funerals were all free of charge. Funding was provided by charity subscriptions, donations, and interest on the endowment fund.

The part that is unclear is how the “property and effects” portion was carried out or exactly what it covered. Clearly, if a woman inherited land, the implication would be that the Home for Aged Protestant Women would be entitled to it. However, Elizabeth did have spending money. So, they didn’t seem to take that from the women. It is also unclear what happened to their personal effects upon their death.

Living At The Home For Aged Protestant Women

The Home Itself

On March 3, 1874, Elizabeth moved into the HAPW. It was a one hundred feet by forty feet brick building, which contained three floors and a basement. Elizabeth could enjoy the common spaces that included the parlor, chapel, sitting room, and dining room. Her bedroom was one of thirty-seven bedrooms in the facility, although when she moved in under twenty were in use. Additional rooms included the kitchen, a room for baking, two pantries, four rooms for provisions, a laundry, a drying-ironing room, two rooms for clothes, and two bathrooms.

The home even had an elevator and fire escapes. The large solid fire escapes were designed to make exiting in as emergency as easy as using a regular staircase. This was critical given many of the residents’ step wasn’t what it had once been.

The rooms in the home were large and spacious. The thick carpets, paintings on the wall, furniture, and knickknacks would still be in use years later. The bedrooms were beautifully furnished with churches in the area donating money for many of the furnishings. By the 1900s, the rooms in the house were described as “old-fashioned comfort.”

Daily Routine

The women spent their days entertaining each other, napping, or pursuing personal interests. Elizabeth definitely kept busy. She went out a lot, but also spent a good deal of time in her room. She wrote letters daily and spent a good amount of time reading.

However, she was often found in her rocking chair making various items including: pin cushion covers, silk stockings which she knitted, lace ties, and wash cloths. Some she used, such as, the silk purse that she carried. Some gifted to friends and family. Others she sold. In her later years, she shared that “she never has been able to get along without plenty of spending money and never will.”

If bored of other activities, the women could just take in the sights of the property: the huge shade trees, manicured lawns, and gardens. The live-in gardener and his crew could be seen tending to the property to keep it looking proper. Other times they could watch workmen on the property, such as, in 1882 when a significant expansion was undertaken.

When it was mealtime, she joined the other ladies of the house in the dining room. It was an elegant affair. Tables were adorned with perfectly white cloths, china, silver, and flowers. Sparkling water was provided from the facility’s private spring.

A Christian facility would be amiss if it did not provide Sunday services in the Chapel. Thus, ministers in the area took turns bringing the word to the women of the HAPW. Occasionally, the women were graced by entertainment. And, of course, there were visitors to the facility.

Kept on Going!

On Elizabeth’s 98th birthday, family and friends called upon her with the youngest two visitors being Carolyn and Hortense Klinefelter, her great-grandson Judge Klinefelter’s (Rod’s great-great grandfather) youngest children. Family, friends, and observers thought she just might make one hundred since she seemed as strong as ever and didn’t seem to slow down. Read more about Judge Klinefelter.

In the fall of 1900, Elizabeth was described as looking like a well-kept seventy-year-old. According to a reporter, she had “bright eyes and rosy cheeks and nimble fingers.” He went on to say, “She has a face so serene and a heart so contented that they are sort of magnets to attract all bright things her way.”

Elizabeth still took care of herself. And, although she wore glasses, she was known for always looking over the top of them. She said that he needed glasses no more now than when she was young. And, the article said that she still had her second sight. I am suspecting that they meant that she still had her women’s intuition.

Her door was almost always open during the day. Inside the sunny room, Elizabeth could be seen busy knitting, reading, or writing. On the wall, was a 5-generation photograph. It seems very possible that it was of Elizabeth, her daughter Ann Rue (Brooks) Klinefelter Hendrickson, her grandson Joseph Gazzan Klinefelter, great-grandson Judge Sharpless Klinefelter, and one or more of Judge’s daughters. There are other possibilities, but for various reasons this option seems to rise above some of the others.

Change In Routine

Still, Elizabeth’s routine had changed a little over the years. She didn’t get around as easily as in the past as one of her knees gave her trouble. Thus, going out was no longer part of her regular routine. Elizabeth’s visiting was mostly limited to the ladies near her room on the first floor.

The facility had also changed over the years. For instance, it now had electric lights. Additionally, a large addition of bedrooms was added in the 1880s and the addition of a second dining room. It now was home to over fifty women. Likely other rooms had also been added in the addition to support the daily routine and care of the inmates at the HAPW.

In the summer of 1901, Elizabeth was unwell to the point that she took to her bed. It was the first time she had done so in the many years that she had lived at the home. They thought for a moment that this might be the end, but she rallied and became her bright, cheerful, industrious self, once again.

Keys to A Long Life

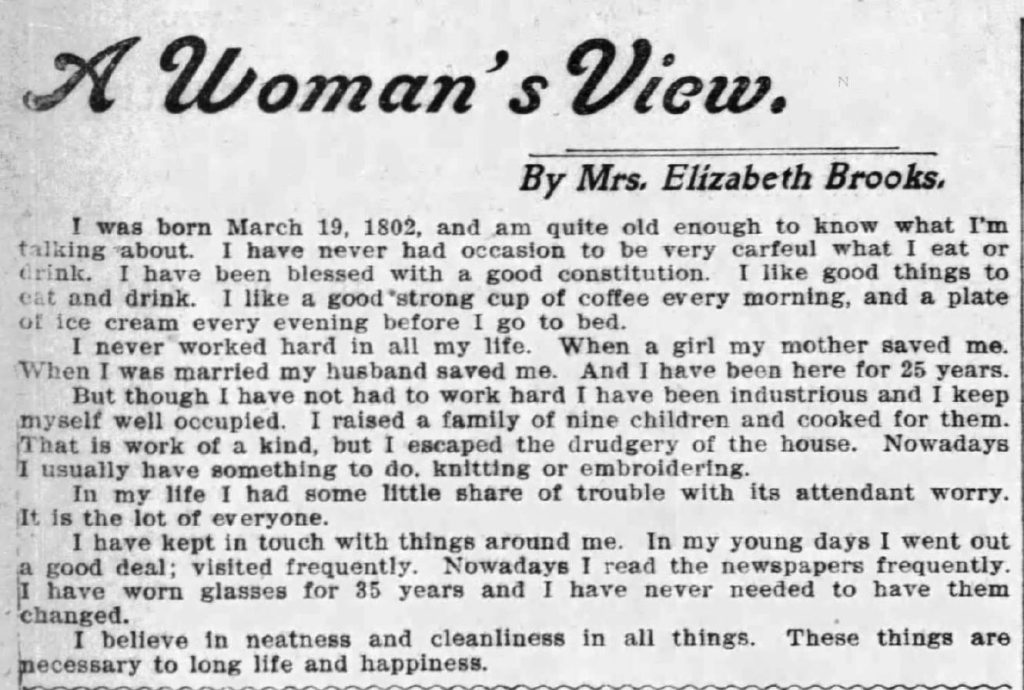

Elizabeth’s keys to a long life seem to be not working too hard, having a strong constitution, and avoiding too much worry. She said that she never had to watch what she ate or drank. And, she always stopped working when she was tired. Read about it in her own words in the adjacent newspaper image. This was printed August 11, 1901, less than a month before she died. Notice: At 99 she got her own byline.

The only odd thing in the article is that it says she raised a family of nine children. Records have only been found for six children and I suspect this is a typo or misunderstanding of what Elizabeth said. She was raised in a family of nine children, but appears to have had raised six children. Being the youngest of her siblings and marrying at age 20, it seems that she wouldn’t likely have been the cook in the family, but you never know.

Through it All

Born shortly after Washington D.C. became the Nation’s capital, Elizabeth lived through the presidencies of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James Polk, Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, James Buchanan, Abe Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, Ullysses S. Grant, Rutherford B. Hayes, James A. Garfield, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland (twice), Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley.

Those years were a time of great invention. During Elizabeth’s life, some of the major inventions include: gas and electric lighting, tin cans, the steam locomotive, photographs, the typewriter, stethoscopes, the sewing machine, the revolver, the telegraph, Morse Code, the internal combustion engine, dynamite, traffic lights, barbed wire, the telephone, the vacuum, motor vehicles. All of these are important to our lives today.

At the time that Elizabeth died, she was only six months shy of her hundredth birthday! Quite a feat in days when so many did not survive childhood. She had lived through the War of 1812, the Mexican-American War, and the Civil War. See had also experienced people heading west during the Gold Rush. Additionally, she had lived through the loss of her parents, all her siblings, her husband, and at least two children.

Afterward

The name of the facility was later changed to Rebecca Residence. However, it appears to have continued the same vision. While doing the research for this story, I discovered a Finding Aid for the records for Rebecca Residence. The records are housed at the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Interestingly, the records go back to the founding of the facility and even include applications for admission and visitor logs. This is another of many reasons to make a trip to the Pittsburgh area.

The Rebecca Residence moved to a new facility in 1999. According to the History of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, the original building became 3 Rivers Center for Independent Living. Today, Google Maps shows a sign in front of the building at 900 Rebecca Avenue that says, “Community Psychiatric Centers.”

I think Jane Holmes would be impressed that her vision was realized and that although in use in different ways, the facility she helped open is still in use after 150 years.

Featured Image: Pittsburgh Post, October 21, 1900

Prompt: Institution

#52ancestors52weeks