In 1698, Thomas and Grace Pearson decided to move their family to America. It was a decision that would turn deadly.

Life In England

On April 24, 1679, Thomas Pearson, a linen draper (fabric merchant), of Keighley, Yorkshire, England married Grace Veepon. The couple married in a quiet Quaker ceremony at the home of her parents John and Elizabeth Veepon in Briercliffe, Lancashire, England (marked in pink on map). Assuming they lived in the same home as they did in 1662, it was quite large, having five hearths. It was one of three homes of this size. The only house that was larger was Extwistle Hall. It had 11 hearths.

Grace’s parents, James Veepon, and Edward Veepon were all in attendance. However, according to the records of the Marsden Monthly Meeting no one with the Pearson name is listed among the attendees. Keighley was some distance away, but it wasn’t so far as to prohibit any travel. It likely was a matter of his family not belonging to the Society of Friends.

After their marriage, Thomas and Grace settled into their home in Keighley, but continued their association with the Marsden Monthly Meeting. In the coming years, Thomas and Grace would have three daughters: Grace, Elizabeth, and Sarah. Grace was born on May 31 of the year following their marriage. Elizabeth came along two years later on March 25, 1682. And, finally Sarah on October 15 1684. Their three daughters’ births were all registered in Keighley.

America Bound

Certificate of Removal

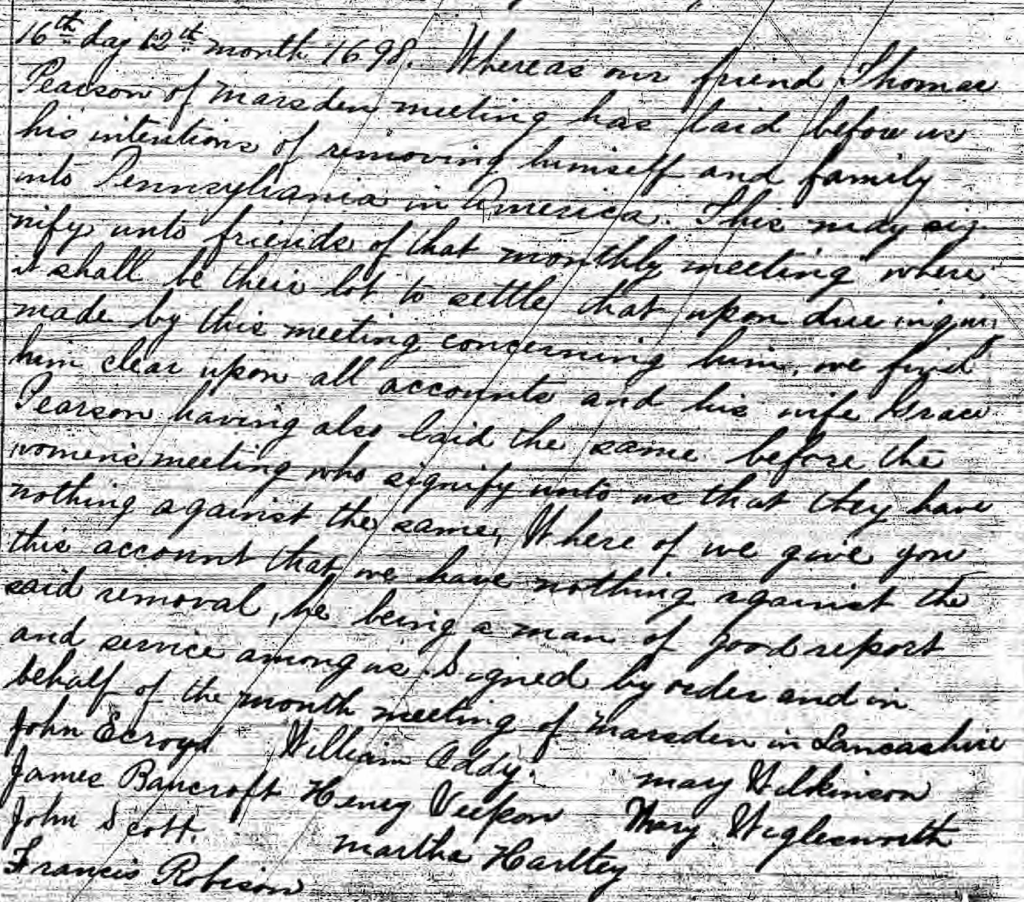

On August 20, 1698, Thomas Pearson informed the Marsden Monthly Meeting that he intended to remove his family to Pennsylvania, America. The reason for the move was not directly stated. However, the family was going on the journey with other members of the Society of Friends. The Lancaster Meeting had chartered the Britannia to take Quakers to America. Many friends from surrounding meetings joined the voyage.

It is likely that the Quakers were moving to America to gain religious freedom. Although some leniency in religion had been allowed more recently, Quakers were still required to take oaths and pay tithes to which they objected. It is not known if Thomas had simply paid the tithes or objected like many others who attended the Marsden Meeting. However, it is likely that he had objected and been punished as this was the case for his father-in-law John Veepon.

John Veepon’s Persecution

Prior to Thomas and Grace’s decision to make America their new home, John had spent considerable time in prison. His crime was refusing to pay tithes and to take oaths as they were against his beliefs as a member of the Society of Friends. In 1676, John had a piece of kersey (coarse wool cloth) taken from him for payment of tithes. It was valued at one pound and 10 shillings.

By 1682, the Church of England had strengthened their penalties for non-payment of tithes. That year ten individuals, including John Vipon were prosecuted in the Ecclesiastical Court of Tithes. They were prosecuted based on suite brought by Edmund Ashton of Whalley (marked with light green on map). Mr. Ashton was described as an impropriator, a layperson who possesses church property. They were excommunicated from the Church of England and received an “excommunicatus capiendus,” which required them to be arrested and imprisoned until they made amends with the church.

It is unclear how long they served, but they were out of prison by the fall of 1684, as on September 1 of that year, John and eight others from the Marsden Meeting were back in court at the request of Edmund Ashton. Upon refusal to take the oath, which they did not believe in, they were again committed as prisoners. They were imprisoned at Lancaster Castle until August 23, 1686 when released by proclamation of King James II.

Just over a year later, John and 18 others from the Marsden Meeting were back in Court again at Mr. Ashton’s request. On October 4, 1687, they were in the Bishop’s Court at Chester. Again they refused to take the oath and they were imprisoned. They were held until August 22, 1688 when King James II again freed them.

John had a slight reprieve. Then on April 28, 1691, John and 31 friends from the Marsden and Rosedale meetings were imprisoned. Six of them died “for their testimony”. I am not sure, but this wording implies to me that they might have received this as their sentence. In June 1695, King William granted John and the other prisoners a general pardon. They were finally released after serving four years.

The only question this raises in my mind is, “Why didn’t Thomas take Grace’s father with them to America?”

Preparations to Set Sail

Thomas got his affairs in order for the move. I am not sure if he owned property, but being a merchant, it is likely that he had property – land, home, or furnishings to dispose of before the journey to America. During the months that Thomas and family were preparing for the move, the Marsden Meeting investigated, as they always did before a person moved from the area to ensure they were in good standing and that all debts had been paid. They found the family to be in good standing. On February 16, 1699, the meeting provided the family a certificate that they could present to their future Quaker meeting in America.

The family traveled to the port at Liverpool (marked in green on the map), taking whatever goods that they intended to take to America. On April 16, 1699, they began loading goods that were being transported to America for commercial purposes on board the Britannia. Only ten men shipped goods to America, most of them also sailed on the ship. It is not known if Thomas planned to continue as a fabric merchant in America. If he did, then he likely was one of the 10 men shipping this type of goods.

By May 5, the loading of commercial goods was complete. Then, the passengers and their personal goods were loaded on board. Ready to set sail, Richard Nicholls guided the Britannia out of the port at Liverpool. The ship sailed for Cork, Ireland, arriving May 20. In Cork, they obtained provisions before heading out to sea.

At Sea

At the time, it typically took about eight weeks to travel from Liverpool to Philadelphia. However, the Britannia was significantly slower in crossing the Atlantic, taking approximately 13-14 weeks to make the journey. The ship wasn’t the fastest available and they had likely encountered winds that were unfavorable to swift travel.

Additionally, the ship appeared to be overloaded with both passengers and goods. The ship’s capacity was 140 passengers. However, 145 people have been identified as sailing on the ship and this is not considered a full list. It is believed that over 200 people may have been on board.

Thus, before they reached Philadelphia, the provisions on board ran low. This was especially challenging because it was very hot and dry during their journey. One man wrote home that the passengers were very thirsty and that the ship did not have enough water and beer. Even if they prepared for a delay in the travel, it is unlikely that they would have brought on board enough liquid for such a long journey.

The Sick Ship

During the journey illness raged on the ship. It is unclear exactly what ran rampant through the ship. Some people reported it to be smallpox. Others said that people had fever, dysentery, and jaundice. However, records indicate that it was likely Typhus, which was also known as “Ship Fever.” Typhus was highly infectious and was common in that era on crowded immigrant ships. Poor sanitation was a major contributor to the disease, which was transmitted by lice.

The illness was definitely severe and it was reported by those traveling that over 50 people died before the ship docked in America. The group most greatly impacted were the men, followed by women. Children and young adults were the least affected.

Thomas Pearson was among the men who perished on board the Britannia.

Arrived

Once in America, the Britannia stopped at a couple of ports (maybe more) to allow passengers to disembark before reaching its final destination. The ship finally reached Philadelphia on August 24, 1699.

More Illness and Death

Many of the passengers arrived sick and weak. Unfortunately, arrival on land did not mean the end of illness and death. Twenty more passengers succumbed, including Grace Pearson. Grace died on September 14, 1699, three weeks after their arrival.

It is assumed that Grace was ill at the time of arrival. However, a Yellow Fever epidemic was also raging in Philadelphia at the same time. It seemed to rage, then calm, then rage again. It was so bad around the time the Britannia arrived that all business in the city was suspended. Many deaths, however, occurred in September with many among members of the Society of Friends. Thus, the illness that led to Grace’s death could have been contracted on the ship or on the shore.

In total, twenty more people on the Britannia died within weeks of arriving in Philadelphia. When word got back to England about the fate of so many on board the ship, the Quakers in the are recorded “that all Friends who are concerned in transporting people into foreign parts take care not to crowd them together in ships to prejudice their health or endanger their lives.” It is said that no Friends from Lancashire moved to America for some years to come.

Orphan Daughters

Thomas and Grace’s three daughters, ages 19, 17, and just shy of 15 found themselves alone in a strange land, having lost both parents in a matter of weeks. Fortunately, the members of the Society of Friends in Philadelphia and other nearby areas stepped up to care for the sick and assist the widows and children. However, this led to the sisters being split up. Grace, who was nineteen, stayed in Philadelphia and was cared for by the Philadelphia Meeting. Meanwhile, Elizabeth and Sarah were cared for by the Neshaminy/Middletown Meeting in Bucks County. (Note: In this time period, this meeting was called Neshaminy in some records and Middletown in others. F or readability, Middletown will be used herein.)

It is unknown who took in the the three teenage orphans. An Edward Pearson family lived in Bucks County, Pennsylvania at the time. Edward was from Wilmslow, Cheshire, England (blue dot on Lancashire map), some distance away from Thomas and Grace’s previous home. No evidence, however, has been found to indicate that they are related or that they had a hand in caring for the teenager girls.

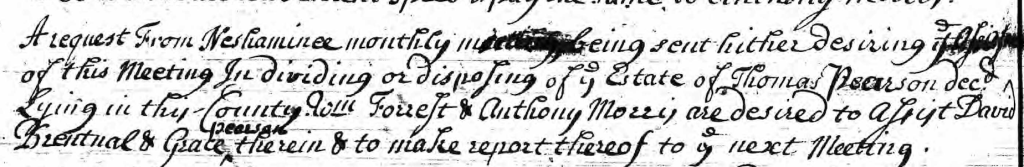

Settling Thomas’ Estate

Upon learning that Elizabeth and Sarah were in their midst, the Middletown Meeting requested that William Hayhurst, a prominent member of the meeting, arrange for Sarah and Elizabeth to provide their father’s certificate from their prior meeting as soon as practical. They also asked Mr. Hayhurt to send a request to the Philadelphia Meeting to have Thomas Pearson’s estate distributed. This request was likely made in order to obtain funds for Elizabeth and Sarah’s living expenses.

Being the oldest, Grace was responsible for distributing her father’s estate. However, she was a single female and only 19 years of age. Therefore, the Philadelphia meeting assigned David Brentnall to assist her in settling the estate. Before Grace married in May 1700, the Philadelphia Meeting requested that David Brientnall, Anthony Morris, and William Forrest attempt to get Thomas Pearson’s estate settled, if possible, before Grace’s marriage.

I have not found anything as to the size of the estate or what it may have included. However, many of the people who came to Pennsylvania in the 1600s had already purchased land before they made the journey across the sea. So, it would not be surprising if he owned property in Pennsylvania. In addition, since he was a fabric merchant, it is possible that he had fabric that he intended to sell. Thomas and his wife also likely brought some personal items that also had to be distributed.

Elizabeth

(March 25, 1682 – August 21, 1743)

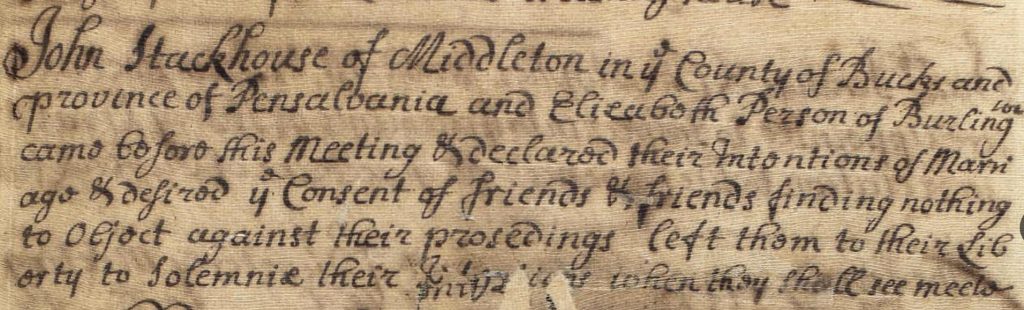

On September 4, 1702, Elizabeth Veepon Pearson married John Stackhouse. John was also an Englishman and member of the Society of Friends. He had come to America in 1682 with his uncle and his brother.

It is from Elizabeth and John, that Rod’s family line descends. At the time of their marriage, Elizabeth appears to have been living in Burlington, New Jersey. Meanwhile, John Stackhouse is living in Bucks County, only a few miles away across the Delaware River. Their marriage intentions were presented at the Burlington Monthly Meeting in Burlington, New Jersey. What Elizabeth was doing in New Jersey is unknown. However, since her sister Sarah also lived in Burlington and Elizabeth and John stated their marriage intention in the Burlington Quaker, it suggests that her stay in Burlington was a bit longer term. It is possible that the family they were living with in Bucks County moved to the area.

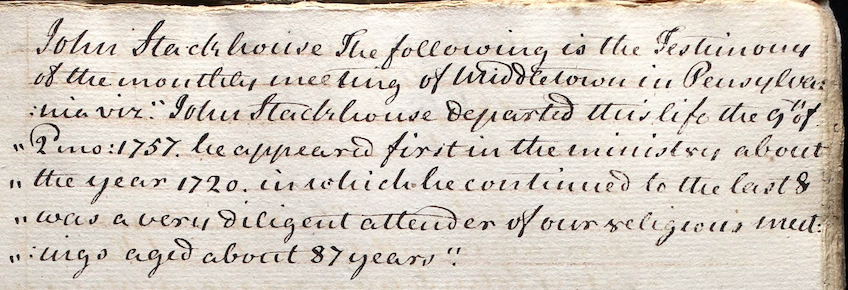

John and Elizabeth settled in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. They were the parents of nine children, including Thomas Stackhouse from whom Rod’s family descends.

Elizabeth died August 21, 1743 at Middletown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. She was 61. Elizabeth is buried at the Middletown Friends Cemetery. John outlived Elizabeth by fourteen years, dying in 1757.

Grace

(May 31, 1680 – April, 1719)

In 1700 Grace and Robert Heatom went the the Quaker approval process to get married, declaring their intention to marry at the Philadelphia Monthly, Meeting. On May 8, 1700, Grace married Robert in Bucks County and it was recorded in Middletown Monthly Meeting records. Robert had also been on the Britannia, having gone to England on business.

In attendance at the wedding were her sisters, Thomas Stackhouse Sr., Thomas Stackhouse Jr. and a large group of other members of the Society of Friends. Elizabeth would later marry Thomas Sr.’s nephew John, who was the brother of Thomas Stackhouse Jr.

Grace and her husband Robert had nine children. However, in 1719, disease struck the family. Grace died in April. Over the coming months, her five youngest children followed her to the great beyond.

Sarah

In 1707, Jonathan Woolston married Sarah Pearson, of Burlington, New Jersey. They had several children.

An interesting note is that Jonathan Woolston’s brother-in-law John Stackhouse was a witness to his will. Based on information found, it seems that Sarah, Elizabeth and their husbands remained close throughout their life.

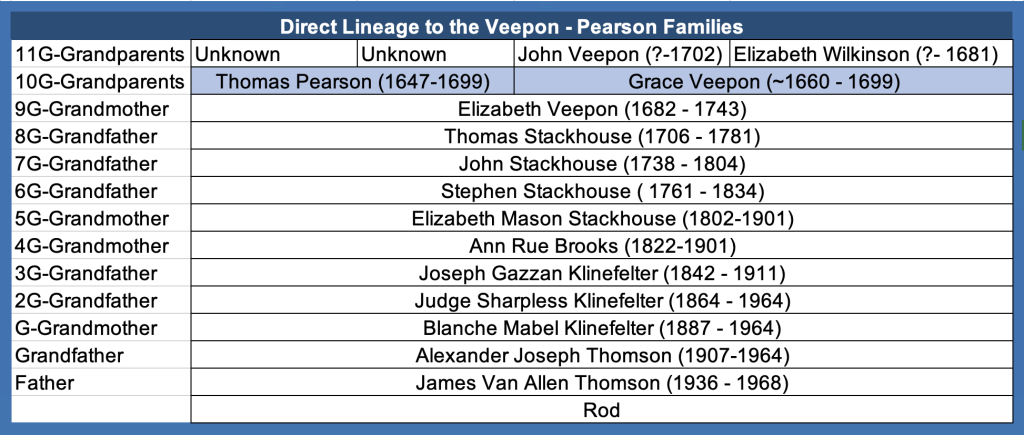

Lineage

The following chart shows Rod’s relationship to the Pearson, Veepon, and Stackhouse families. It is important to note that the Veepon name is recorded with many different spellings. Some of the spellings found in records are Veepon, Viepon, Vipon, Vipond, and Vipont. Pearson is also recorded as Pierson. Clearly the early generations are quite distant relatives, but are also an important part of his English Quaker ancestry.

Featured image: By WikiImages via pixabay.com

Prompt: Water

#52ancestors52weeks