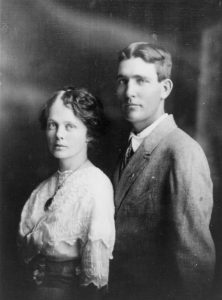

Above Image: Xavier and George Wittmer

What do ice elevators, recording devices for fluid meters, gas meters, and a device for turning bolts and screws have in common?

The Simple Answer

All of these devices were either invented by or had novel enhancements made by the Wittmer family of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The inventor listed on the patents for these devices were the brothers and nephews of Rod’s 3rd great-grandmother, Elizabeth (Wittmer) Ackerman.

Why such diverse inventions?

Before they came to America, their father Franz Xavier Wittmer had tried his hand at multiple occupations. He had been a farmer, miner, and a tailor. He found none of these occupations to be very profitable. His sons, George and Xavier, carried on in his tradition of searching for profitable business ventures. Their business focus led the Wittmer family to own and invest in several businesses operating in and around Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Each of these businesses had specific needs and, in all cases, the Wittmer family desired efficiency.

The Companies

Wittmer Ice Company

Wittmer Ice Company

The first significant company that George and Xavier Wittmer created was the Wittmer Ice Company. They started their business in 1872 by renting an ice house that was already in existence. The business was profitable and the brothers purchased a large tract of land.

On that land they made large ponds and built 11 large ice houses. It was estimated that 20,000 pounds of ice were gathered and stored there each year.

Xavier invented enhancements to ice elevators. His ice elevator used one continuous chain instead of two and could have a variable number of hooks as needed. He made four specific claims of invention in his patent granted December 23, 1875.

Wittmer Brick Company

In 1884, the Wittmers established the Wittmer Brick Company seven miles outside the city. The hillside had extensive clay deposits, perfect for making bricks. And, the Pittsburgh and Western Railway ran through the area, perfect for shipping bricks. The location became known as Wittmer, or sometimes referred to as Wittmer Station.

In 1897, The Clay Worker, the Official Organ of the National Brick Manufacturers’ Association of the United States of America, highlighted Wittmer Brick Company’s brick making process. It was quite complicated with numerous steps. They used gas to heat the kilns. It wasn’t common in the United States, but it was used in Germany, where the Wittmer family originated, for finer pieces, such as terra cotta.

The Wittmer works also had a novel incline railroad to move the bricks from the kiln to the railroad freight cars, some 25 feet lower. It was designed so that as a car loaded with bricks comes down to the railroad platform, an empty car is pulled up from the platform to the kiln. This process was very efficient and greatly decreased the effort required to move the bricks from the kiln to the freight car.

The business was incorporated January 1, 1901. At the time, the Wittmer Brick Company was all in the family with Xavier, his son, and his brother George’s 3 sons all involved in the business. George, who was much older than Xavier, was retired.

At the time of incorporation, the company was described as makers of brick, tile, terra cotta, and other similar products. It was a reorganization of the company as it had stood and had its headquarters in Pittsburgh with the “works” at Wittmer Station. The primary reason for reorganization was for it to issue stock.

American Natural Gas Company

In 1889, the Wittmers and some of their associates formed the American Natural Gas Company, with the Wittmers having a controlling interest. The founders all used large amounts of gas in their other businesses that they owned. They believed it would cost less and be more efficient to go together and create their own gas company rather than their current situation. The plan was to pay the company to supply themselves, sell gas to others, and profit from it as shareholders.

They started out with 700 acres of land in an area about 10 miles north of Wittmer Station. They hit their first gusher in July and planned to have pipe laid and operational by the end of the fall.

Xavier’s son George X. Wittmer became the secretary/treasure of the company. He also invented several devices for use in the gas business. One of those inventions was a recording apparatus for fluid meters granted December 30, 1902. It measured both pressure and volume flowing throw it.

Xavier’s son George X. Wittmer became the secretary/treasure of the company. He also invented several devices for use in the gas business. One of those inventions was a recording apparatus for fluid meters granted December 30, 1902. It measured both pressure and volume flowing throw it.

In 1925, Xavier’s brother George’s son Henry was running the company and it was valued at $14,000,000 (nearly $250m in today’s dollars). The following year Wittmer Oil & Gas Properties was formed with Henry as president. American Natural Gas Company was reorganized and some properties sold off. It became a subsidiary of Wittmer Oil & Gas Properties. By this time the Wittmers had or had previously had interests in Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, New York, and Michigan under multiple company names.

The family sold controlling interest in the company in 1942.

American Telephone Company

The American Telephone Company was chartered in 1897. Xavier and Henry Wittmer were two of the directors of the company. Their interest in having a telephone company was to provide communication to their business interests. Since they had gas right of ways, they could lay the telephone lines in the same area. Thus, no additional land needed to be acquired or set aside. Thus, this venture required minimal capital.

The Big Fire

Out of necessity, the Wittmer’s businesses were situated along the Pittsburgh & Western Railway. Their location provided them ease of shipping their goods, but it would also cause the end to some of their businesses.

On May 19, 1903, a train went down the tracks and a spark flew into a freight car of oats that was near the glass works on the Wittmer property . Very quickly the fire spread to the glass works. Before the local people were able to knock the fire down, half of Wittmer had burned. The Wittmers lost their brick manufacturing facility and their ice storage houses.

Profitable

When Xavier died in 1921, he left a $630,000 estate (over $11.5 million in today’s dollars), including a summer home in Atlantic City. He had invested in his family’s businesses and served as president of their gas and brick companies. Additionally, Xavier had been a member of the board and a vice-president of North American Savings Company. It was formed in 1901 and grew from $350,000 in capital to $2,000,000 in a couple of years. Similarly, he had become a member of the board and vice-president of Merchants Savings & Trust when it was formed in 1903.

Xavier and George had achieved their father’s vision of a successful business by creating new businesses, creating new technology to support those businesses, and by grooming their sons to work with them and carry on those businesses.

Wittmer Ice Company

Wittmer Ice Company

His Career

His Career

Trouble

Trouble